The Reality Of Our Fine-Tuned Universe Presents An Insurmountable Obstacle For Scientists

Our Universe From A Multiverse?, Copyright, RCR

Our Universe From A Multiverse?, Copyright, RCRRoger Penrose is indeed a brilliant physicist and mathematician, whose work has deeply influenced cosmology, particularly in areas like the nature of singularities and the fine-tuning of the universe. His assertion of the multiverse as a possible explanation for the origins of the cosmos, rather than attributing it to an infinitely intelligent Being, stems from several philosophical and scientific perspectives:

See The 75 Scientists Who Believe God Created The Universe

Adherence to Naturalism

Penrose, like many scientists, operates within the framework of methodological naturalism, which seeks explanations for phenomena solely through natural processes, without invoking the supernatural. This commitment often leads to exploring models like the multiverse, which are viewed as extensions of physical theories rather than theological propositions.

Philosophical Avoidance of a Divine Creator

Acknowledging an infinitely intelligent Creator has profound philosophical and metaphysical implications. It directly confronts questions of purpose, morality, and the nature of existence, which many scientists prefer to avoid within the confines of scientific discourse. Penrose’s preference for a multiverse may reflect a reluctance to step into theological or metaphysical territory.

Theoretical Support from Cosmology

The multiverse hypothesis is often tied to certain interpretations of quantum mechanics, inflationary cosmology, and string theory. While these ideas are speculative and not empirically verified, they provide a framework within existing physics for explaining fine-tuning. Penrose has critiqued aspects of inflationary cosmology, but his views on the multiverse suggest he finds it a more scientifically palatable explanation than positing a Creator.

The Fine-Tuning Problem

Penrose has highlighted the extraordinary improbability of a universe fine-tuned for life. For instance, he famously calculated the low entropy state of the Big Bang to have a probability of 10^{-10^{123}}. Such numbers seem to demand an explanation. The multiverse offers a way to “dilute” the improbability: if there are infinite universes with varying parameters, then one might randomly have conditions that support life. This sidesteps the need for an intelligent designer. The problem for Penrose in his publishing of this immense number is that he has cornered himself into an impossibility that the multiverse cannot solve. Even if the multiverse did exist, though there is no scientific proof it does exist, this would not solve the question of origin or source, but make it infinitely more complex. The greater the complexity of the universe in its source and origin, the greater the need for intelligence, rather than a random unguided event.

Resistance to Theological Implications

Accepting a Creator introduces a “final explanation” for the cosmos, which some scientists see as halting further inquiry. Penrose, who values intellectual exploration, might resist such an explanation because it appears to close the door on alternative models or deeper scientific understanding. We now observe what happens when science is confronted with stunning evidence for the existence of God in the very origin of the Cosmos. Faced with a decision that proves an intelligent Creator as the source of the universe, many scientists resort to a far more difficult conclusion: complexity beyond reasonable. While science has consistently relied on the simplest of explanations in the past to define complex systems, faced with God as the answer for the Cosmos, a great number of scientists today resort to a complex answer that cannot be proven.

Counterpoint: The Simplicity of a Creator

From a philosophical standpoint, Occam’s Razor might favor a single, intelligent Creator over the immense complexity of an infinite multiverse. The multiverse requires layers of assumptions and theoretical constructs that are far from empirically verified. A Creator, by contrast, provides a unified, coherent explanation for fine-tuning, the origin of physical laws, and the existence of the universe.

The Role of Worldview

Ultimately, Penrose’s preference for the multiverse over a Creator reflects his worldview rather than the insufficiency of the Creator hypothesis. His intellectual brilliance does not preclude theological reflection, but his scientific and philosophical commitments lead him to prioritize naturalistic explanations.

It’s worth noting that some scientists who have confronted the same evidence for fine-tuning have come to different conclusions. For example, thinkers like John Polkinghorne, Francis Collins, and others see the fine-tuning as compelling evidence for a Creator, rather than a multiverse.

Roger Penrose’s Critiques of Inflation and Contributions to Fine-Tuning Discussions

Critique of Inflationary Cosmology

Penrose is a vocal critic of the inflationary model, a cornerstone of modern cosmology that posits an exponential expansion of the universe moments after the Big Bang. While inflation is widely accepted for explaining the uniformity of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and the large-scale structure of the universe, Penrose finds it problematic:

Fine-Tuning of Inflationary Conditions

Penrose argues that inflation doesn’t solve the fine-tuning problem but shifts it to the conditions needed to initiate inflation itself. He points out that for inflation to work, the universe must have started in an incredibly specific and highly improbable low-entropy state. This, he suggests, undermines inflation’s explanatory power because it doesn’t address why such an initial state existed.

Scientific Evidence For God: A Fine-Tuned Universe

The Measure Problem

Penrose critiques the lack of a clear measure in the space of all possible inflationary scenarios. Without a robust mathematical framework for distinguishing probable from improbable outcomes, he questions the reliability of inflation as an explanation for the universe’s properties.

Incompatibility with Observed Fine-Tuning

Penrose has highlighted that the fine-tuning required for inflation to occur is even more improbable than the fine-tuning of the universe itself. This is evident in his famous calculation of the phase-space volume of the Big Bang’s initial state, which he estimates at 10^{-10^{123}}. For Penrose, this calculation suggests a need for an explanation that goes beyond inflation.

Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC)

In response to these issues, Penrose proposed his own model, Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC). This model offers an alternative explanation for the universe’s origin and attempts to address the fine-tuning problem:

Eternal Cycles of Universes

In CCC, the universe undergoes infinite cycles or “aeons.” Each aeon begins with a Big Bang and ends in an eventual “stretching out” of spacetime due to the dominance of dark energy. At the end of an aeon, spacetime becomes conformally smooth, and a new aeon begins.

Eliminating the Need for a Singular Beginning

CCC avoids a singularity at the Big Bang, providing a naturalistic explanation for the universe’s initial conditions. Penrose argues that the conformal smoothness of spacetime at the end of one aeon leads to the conditions necessary for the low-entropy start of the next aeon.

Observational Evidence

Penrose and collaborators have claimed to identify evidence for CCC in the CMB. They suggest that concentric circular patterns in the CMB could be “imprints” from previous aeons. However, these claims remain controversial and are not widely accepted by the cosmological community. As you can see, so far, Penrose must take great assumptive license in order to assert these ideas. None can be proven by science, but exist primarily as a way to deny a Creator with infinite intelligence as the source of our universe.

Penrose on Fine-Tuning

Penrose is deeply concerned with the fine-tuning of the universe, particularly its low-entropy initial state. In this he posits several naturalistic solutions, without objective evidence.

The Weyl Curvature Hypothesis

To explain the universe’s extraordinary low entropy, Penrose proposed the Weyl Curvature Hypothesis, which asserts that the Weyl curvature tensor (describing the tidal forces of spacetime) must be zero at the Big Bang. This condition ensures a smooth, uniform start to the universe and avoids chaotic initial conditions.

Improbability of the Big Bang

Penrose calculated the odds of the Big Bang’s initial state arising by chance as 10^{-10^{123}}. This number underscores the extreme fine-tuning required and raises profound questions about why such a state existed. Penrose sees this as a key challenge for any cosmological theory, whether it’s inflation, CCC, or something else. What is often unstated is that in this extreme low state of entropy, Penrose admits that this number precludes any chance that a fine-tuned, low state of entropy, could occur naturally. The multiverse does not solve this problem, it merely adds complexity which further requires an infinitely intelligent Being to cause this low state of entropy.

Multiverse as a Response

While Penrose is skeptical of the multiverse as a complete solution, he acknowledges that some view it as a way to explain fine-tuning. The idea is that in an infinite set of universes, at least one would have the conditions necessary for life. However, Penrose is critical of the lack of empirical evidence for the multiverse and its reliance on speculative physics.

It becomes clear to an objective reader that Penrose is looking for a way of escape from the simple answer for why these impossible attributes of our universe exist: A person, not a process.

Philosophical Implications of Penrose’s Work

Penrose’s work highlights the profound questions raised by the universe’s fine-tuning. His critiques of inflation and his development of CCC demonstrate his commitment to addressing these questions rigorously. However, his reluctance to consider a Creator as the ultimate explanation may stem more from philosophical preferences than scientific necessity. We should measure the science that is postulated, with the actual proof that is required, and not yet found.

From a theological perspective, Penrose’s insights could be seen as indirectly supporting the case for a Creator: I have often wondered what Penrose really thinks when he is sitting alone in his office. It must be daunting to have evidence for God and His creation of the universe, but continue to deny this evidence in order to pursue and natural explanation.

The Improbability of the Universe

Penrose’s calculations make a compelling case that the universe’s initial conditions are so improbable that a purely naturalistic explanation is insufficient. This struggle reveals a premise of atheism that is stunning. In asking thousands of atheists over the past 50 years, “If you had evidence that everything presented about Jesus in the New Testament; His miracles that prove He is God; the eyewitness, historical testimony—being found true and reliable—would you become a believer in the God of the Bible?” The answer has consistently been, “No.” This reveals that the decision to deny the existence of God is not evidential, but simply a choice that people make.

The Limitations of Scientific Models

Both inflation and CCC leave unanswered questions about the ultimate origin of fine-tuning, suggesting the need for a transcendent explanation.

Compatibility with Theism

The extraordinary fine-tuning Penrose describes is entirely consistent with the existence of an intelligent Creator who established the universe with precision and purpose.

Comparison of Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) and Other Cosmological Models

Roger Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) stands out among cosmological models as a unique attempt to explain the origins and fate of the universe. The following is a detailed comparison of CCC with other leading models, along with further discussion of Penrose’s Weyl Curvature Hypothesis.

Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC)

Key Features:

- Infinite Cycles: CCC posits that the universe undergoes infinite “aeons,” each beginning with a Big Bang and ending in a conformally smooth state as dark energy stretches the universe to near-infinite size.

- Smooth Transition Between Aeons: The universe’s geometry transforms seamlessly from one aeon to the next through a process of conformal mapping.

- Observational Evidence: Penrose claims to find traces of previous aeons in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), such as concentric low-variance circles he calls “Hawking Points.”

- Eliminates Singularities: Unlike the traditional Big Bang model, CCC avoids a singularity by proposing a transition from the “infinite stretch” of the previous aeon.

Strengths:

- Avoids a beginning singularity, addressing a major issue in the Big Bang model.

- Provides a novel explanation for the universe’s low-entropy initial state.

- Offers testable predictions, though evidence remains controversial.

Challenges:

- Lack of widely accepted empirical evidence for Hawking Points in the CMB.

- Highly speculative, relying on unproven conformal geometrical principles.

The Standard Big Bang Model

Key Features:

- Singular Origin: The universe begins with a singularity approximately 13.8 billion years ago, expanding and cooling over time.

- Inflationary Epoch: A brief period of rapid expansion (inflation) resolves issues like the horizon problem, flatness problem, and monopole problem.

- Cosmic Microwave Background: The CMB provides strong observational support for this model, showing a nearly uniform temperature with slight fluctuations.

Strengths:

- Supported by extensive empirical data, including the CMB, galaxy redshift measurements, and nucleosynthesis predictions.

- Relatively simple and mathematically robust.

Challenges:

- Requires fine-tuned initial conditions, such as low entropy.

- Inflation introduces its own fine-tuning problems, as Penrose critiques.

- Leaves the ultimate origin of the universe unexplained.

Inflationary Multiverse

Key Features:

- Eternal Inflation: Inflation doesn’t end everywhere; some regions of spacetime continue inflating, producing a multiverse with “bubble universes.”

- Anthropic Principle: Fine-tuning is explained by arguing that only universes with life-permitting parameters will be observed.

- String Landscape: Some versions tie into string theory, with each bubble universe corresponding to a different vacuum state in a vast “landscape.”

Strengths:

- Explains fine-tuning without invoking a Creator.

- Potentially compatible with string theory, a candidate for a unified theory of physics.

Challenges:

- Lack of empirical evidence; the multiverse is inherently unobservable by definition.

- Philosophically controversial, as it may dilute the scientific principle of falsifiability.

- Introduces complexity, which some argue violates Occam’s Razor.

Steady-State Model

Key Features:

- No Beginning or End: Proposes that the universe has always existed and maintains a constant average density through the continuous creation of matter.

- Cosmological Principle: Assumes the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales, both in space and time.

Strengths:

- Elegant in its simplicity, avoiding the need for a beginning.

- Initially appealing before evidence of the Big Bang emerged.

Challenges:

- Contradicted by overwhelming evidence for the Big Bang, such as the CMB and the observed evolution of galaxies.

- No mechanism for continuous creation of matter consistent with modern physics.

Penrose’s Weyl Curvature Hypothesis

Core Idea:

The Weyl Curvature Hypothesis (WCH) is a cornerstone of CCC. Penrose proposes that at the Big Bang (or the transition between aeons in CCC), the Weyl curvature tensor—which encodes tidal distortions of spacetime—was precisely zero. This smoothness condition explains:

- The universe’s low-entropy initial state.

- The absence of singularities or chaotic initial conditions.

- The observed large-scale uniformity of the universe.

Significance:

- Provides a theoretical basis for CCC’s cyclic transitions.

- Addresses the fine-tuning of the universe’s initial conditions without invoking a multiverse or inflation.

Critiques:

- The hypothesis is elegant but remains speculative, as the mechanisms enforcing zero Weyl curvature are unclear.

- Relies heavily on assumptions about the nature of spacetime near transitions between aeons.

Theological Implications

Penrose’s CCC and Weyl Curvature Hypothesis, while speculative, highlight the extraordinary precision required to explain the universe’s initial conditions. This raises profound questions:

- Fine-Tuning: The zero Weyl curvature and low-entropy state are compatible with theistic explanations of a Creator who designed the universe with purpose.

- Limits of Naturalistic Models: CCC and multiverse theories, though creative, often face the same challenge of ultimate causation. Why should such a cyclic process or multiverse exist at all?

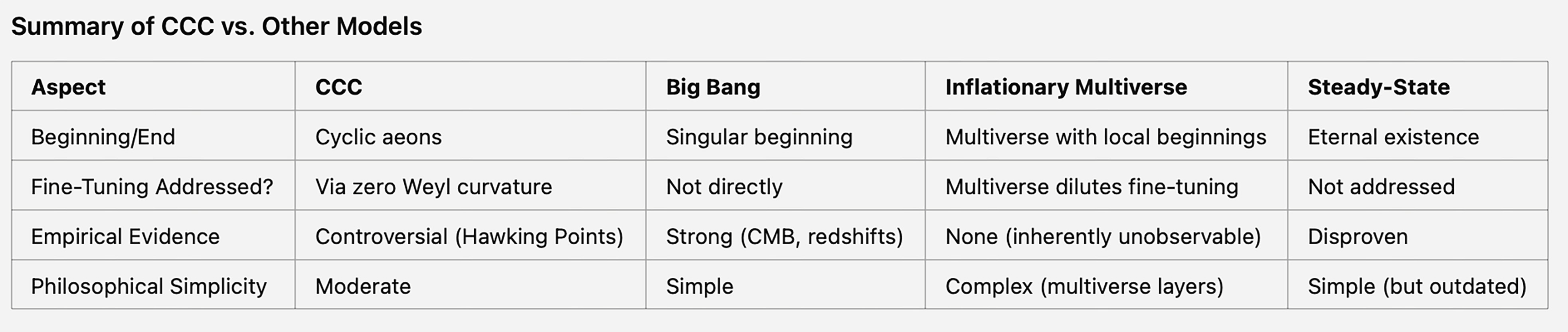

Summary of CCC vs. Other Models

Copyright, RCR

Copyright, RCRAspect CCC Big Bang Inflationary Multiverse Steady-State

- Beginning/End Cyclic aeons Singular beginning Multiverse with local beginnings Eternal existence

- Fine-Tuning Addressed? Via zero Weyl curvature Not directly Multiverse dilutes fine-tuning Not addressed

- Empirical Evidence Controversial (Hawking Points) Strong (CMB, redshifts) None (inherently unobservable) Disproven

- Philosophical Simplicity Moderate Simple Complex (multiverse layers) Simple (but outdated)

Penrose’s Calculations on Entropy and Their Implications

Roger Penrose’s calculations on the universe’s entropy have profound implications for cosmology and theology, as they highlight the extraordinary fine-tuning of the universe’s initial state. Let’s explore his findings in detail and their intersection with theological arguments.

Penrose’s Entropy Calculations

The Low-Entropy Initial State of the Universe

- Entropy is a measure of disorder in a system. For the universe to evolve into its current state, it had to start in an extraordinarily low-entropy condition.

- Penrose calculated the probability of the universe beginning in such a state: P \sim 10^{-10^{123}}

This number is so unimaginably small that it effectively rules out the possibility of the universe’s low-entropy start occurring by chance.

Phase Space Volume

- Phase space represents all possible states of a system. Penrose argued that the initial conditions of the universe occupied an exceedingly tiny volume in phase space, reflecting a state of immense fine-tuning.

- The extraordinary improbability of this initial state directly challenges naturalistic explanations, as it seems to demand a guiding principle or cause.

Theological Implications of Penrose’s Entropy Calculations

Fine-Tuning and a Creator

Improbability and Design: The number 10^{-10^{123}} is so staggeringly small that it suggests intentionality behind the universe’s beginning. A Creator provides a coherent explanation for why the universe began in such a finely tuned state.

Purposeful Design: The low-entropy state allowed for the formation of stars, galaxies, and ultimately life. This purpose-driven framework aligns with the idea of an intelligent Being setting conditions for life to emerge.

The Limits of Chance

Penrose’s calculations starkly contrast with atheistic arguments relying on randomness. The odds are not merely improbable—they are effectively impossible in a single-universe scenario.

The Multiverse Hypothesis attempts to dilute this improbability by positing infinite universes, but as Penrose himself has pointed out, it introduces complexity without empirical support.

Mirroring the Attributes of a Creator

The precision described by Penrose resonates with theological concepts of an omniscient and omnipotent Creator. The ability to fine-tune the universe’s initial conditions reflects the attributes of infinite intelligence and purposefulness.

Comparison with Alternative Explanations

Multiverse Hypothesis

The multiverse suggests that infinite universes exist, each with different physical parameters. Our universe happens to be life-permitting, making fine-tuning a statistical inevitability.

Challenges:

- Empirical Evidence: The multiverse is inherently unobservable and thus scientifically speculative.

- Philosophical Issues: The multiverse raises more questions than it answers, such as the origin of the multiverse itself.

Inflationary Cosmology

Inflationary models propose a rapid expansion of the universe after the Big Bang, smoothing out irregularities and explaining uniformity.

Penrose critiques inflation as requiring its own fine-tuning, failing to solve the ultimate question of why the universe began in a low-entropy state.

Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC)

Penrose’s CCC offers an alternative to fine-tuning by proposing that each aeon naturally evolves into the next, with entropy being “reset” via conformal geometry.

Strengths: Eliminates the need for a singular beginning.

Challenges: Still speculative and requires assumptions about unknown mechanisms in conformal geometry.

Penrose’s Work and Theological Arguments

The Cosmological Argument

Penrose’s work reinforces the cosmological argument for the existence of God:

- Premise 1: Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

- Premise 2: The universe began to exist (evident from the low-entropy initial state and the Big Bang).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the universe has a cause.

This cause must:

- Be timeless and spaceless, as it exists outside the universe.

- Possess immense intelligence, as evidenced by the fine-tuning of initial conditions.

The Teleological Argument (Fine-Tuning)

- The universe’s fine-tuning for life suggests a Designer. Penrose’s calculations demonstrate that this tuning is not just improbable—it’s incomprehensibly precise.

- The alternative naturalistic explanations (multiverse, inflation) are either empirically unverified or philosophically unsatisfying.

Theological Simplicity

While Penrose’s CCC and the multiverse hypothesis attempt to explain fine-tuning, they introduce layers of complexity. A Creator offers a simpler, unified explanation for the universe’s low-entropy start, the existence of physical laws, and the emergence of life.

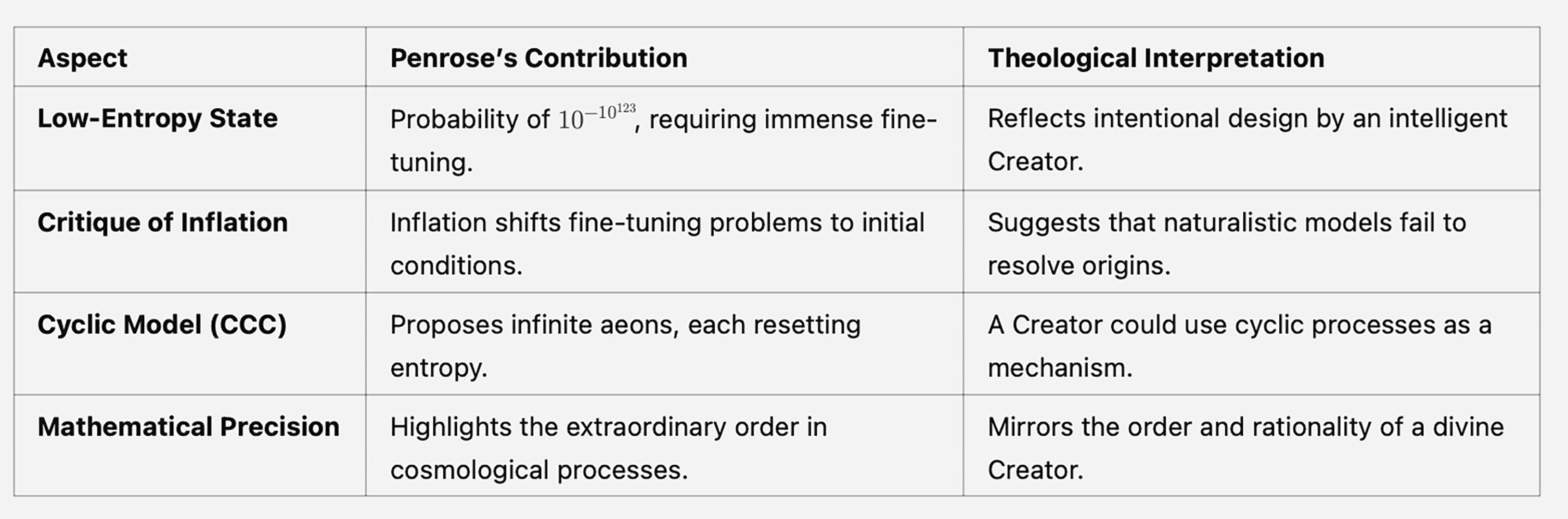

Penrose’s Calculations in Context

Copyright, RCR

Copyright, RCRAspect Penrose’s Contribution Theological Interpretation

- Low-Entropy State Probability of 10^{-10^{123}}, requiring immense fine-tuning. Reflects intentional design by an intelligent Creator.

- Critique of Inflation Inflation shifts fine-tuning problems to initial conditions. Suggests that naturalistic models fail to resolve origins.

- Cyclic Model (CCC) Proposes infinite aeons, each resetting entropy. A Creator could use cyclic processes as a mechanism.

Mathematical Precision Highlights the extraordinary order in cosmological processes. Mirrors the order and rationality of a divine Creator.

Penrose’s calculations on entropy provide some of the most compelling evidence for the fine-tuning of the universe. While his CCC model offers a creative explanation, it remains speculative and raises questions about the ultimate origin of the universe and its governing principles.

Theological arguments for a Creator elegantly address the fine-tuning problem, positing an intelligent Being who established the universe with precision and purpose. The improbability of the low-entropy state described by Penrose aligns seamlessly with the existence of a Creator who intended for life to flourish.

Theological Implications of Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC)

Roger Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) is a fascinating cosmological model that challenges the traditional Big Bang paradigm. While it aims to offer a naturalistic explanation for the universe’s origin and fine-tuning, CCC also opens the door to intriguing theological interpretations. Below, I explore these implications in detail, including CCC’s strengths, limitations, and how it interacts with arguments for a Creator.

Overview of CCC and Its Assumptions

Core Ideas of CCC

- The universe is not a singular event but consists of infinite “aeons” of cyclic evolution.

- Each aeon begins with a Big Bang and ends as spacetime stretches infinitely due to the influence of dark energy.

- At the end of an aeon, all matter decays into radiation, and spacetime becomes conformally smooth. This smoothness allows the transition to the next aeon without singularities or chaotic conditions.

- Entropy resets in each cycle, with no “memory” of previous aeons except faint imprints, such as the alleged Hawking Points in the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

Implications of CCC’s Mechanisms

- CCC removes the need for a singular origin, like the Big Bang in standard cosmology.

- The zero entropy requirement for each aeon’s start is naturally enforced by the conformal geometry of spacetime.

Theological Implications of CCC

A Creator Behind Cyclic Order

Fine-Tuning Persists: Even in CCC, the transition between aeons requires finely balanced mechanisms, such as the zero Weyl curvature hypothesis and the conformal smoothness of spacetime. These conditions could point to a Creator who designed the universe to operate in such a cyclic manner.

Why Cycles?: The existence of infinite aeons, each following strict mathematical laws, raises the question: Why is the universe structured this way at all? A Creator could intentionally design such a process to sustain creation perpetually.

Eternal Cycles Reflect Divine Eternity

CCC’s conception of an infinite sequence of aeons resonates with theological views of God’s eternal nature. The infinite nature of time in CCC could be seen as a reflection of divine eternity expressed through creation.

Purpose and Design in the Cycles

Resetting Entropy: The resetting of entropy between aeons ensures a continuous renewal of order, which aligns with the theological idea of a Creator who sustains creation.

Fine-Tuned Laws: The laws governing CCC—such as the conformal geometry of spacetime—are not arbitrary. They suggest an underlying rationality that is consistent with the concept of a Creator who establishes a cosmos governed by reason and purpose.

Limitations of CCC and the Need for a Creator

Ultimate Origins

While CCC posits an infinite chain of aeons, it does not explain why the system exists in the first place. Why does the universe follow a cyclic pattern? Why do these specific laws of physics govern its behavior?

The contingency of the universe (even in cyclic form) still points to the necessity of a non-contingent cause—a Creator.

Fine-Tuning at Each Transition

The transition between aeons relies on fine-tuning, such as the vanishing of the Weyl curvature tensor. Penrose assumes that this occurs naturally, but why such precise conditions exist remains unexplained in purely naturalistic terms.

A Creator provides a coherent explanation for this order and fine-tuning.

Empirical Challenges

The lack of conclusive evidence for Hawking Points in the CMB weakens the empirical foundation of CCC. If CCC fails to explain observable phenomena, alternative explanations (including theological ones) gain plausibility.

CCC in Contrast to Other Cosmological Models

Copyright, RCR

Copyright, RCRAspect CCC Theological Interpretation

- Infinity of Aeons The universe consists of endless cycles. Reflects God’s eternal nature; cycles as divine order.

- Entropy Reset Entropy is naturally reset at the end of each aeon. Suggests intentional renewal consistent with divine design.

- Fine-Tuning Transition between aeons requires precise conditions. Points to a Creator who fine-tuned the universe’s laws.

- Ultimate Origin Does not explain why cycles exist at all. A Creator is needed to explain why there is something rather than nothing.

Penrose’s Critiques of Naturalistic Multiverse Models

Penrose himself has criticized inflationary cosmology and the multiverse for failing to address the fine-tuning problem:

Inflation Fine-Tuning: Penrose argues that inflation requires its own fine-tuning to work. This shifts the problem rather than solving it.

The Multiverse and Falsifiability: Penrose has expressed skepticism about the multiverse’s scientific validity, as it lacks empirical evidence and introduces speculative complexity.

Key Scientists Opposing the Multiverse on String-Theoretic Grounds

- David Gross: Criticizes the multiverse as a philosophical rather than scientific explanation.

- Paul Steinhardt: Argues that string theory and inflation do not naturally lead to a multiverse.

- Cumrun Vafa: Developed the swampland conjecture, which challenges multiverse-friendly solutions in string theory.

- Roger Penrose: Critiques the multiverse for failing to address fine-tuning in a meaningful way.

While string theory initially seemed to support the multiverse hypothesis due to its landscape of solutions, deeper analysis has revealed significant challenges:

- Predictive Limits: String theory lacks empirical support for a multiverse.

- Fine-Tuning: The multiverse shifts, rather than solves, the problem of fine-tuning.

- Swampland Constraints: String theory’s swampland conjecture narrows the range of viable solutions, potentially excluding many multiverse scenarios.

- Unobservability: The multiverse remains speculative and outside the realm of testable science.

Theological Advantage Over the Multiverse

The multiverse hypothesis often invokes infinite universes to “dilute” the improbability of fine-tuning. However, it doesn’t explain the origin of the multiverse or the laws governing it.

In contrast, a Creator provides a unified explanation for both the existence and fine-tuning of the universe without resorting to speculative and unobservable infinities.

CCC and Biblical Creation

While CCC itself is a naturalistic model, its principles can resonate with certain theological themes:

Renewal and Cycles: The Bible often describes creation as being sustained and renewed by God (e.g., Psalm 104:30, Revelation 21:5). CCC’s cycles could be seen as a metaphor for divine renewal.

Cosmic Eternity: Though the Bible teaches that creation had a beginning, CCC’s infinite cycles could align with the idea of God’s sustaining power throughout eternity.

The Theories of Penrose Have A Concerning Problem: Speculation

Roger Penrose’s CCC provides an intriguing naturalistic alternative to standard cosmology but remains speculative and incomplete. From a theological perspective:

- CCC raises questions about why the universe operates cyclically and why its laws are fine-tuned.

- The resetting of entropy, the infinite cycles, and the elegance of conformal geometry can be seen as reflections of a Creator’s design.

- Ultimately, CCC does not escape the need for a transcendent cause to explain the universe’s existence and structure.

Jesus Creates The Universe, Copyright, RCR

Jesus Creates The Universe, Copyright, RCRIntegrating CCC with Biblical Themes and Theological Cosmological Models

Roger Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) presents an intriguing framework that resonates with certain biblical themes and theological models, despite being a naturalistic proposal. Below, I explore how CCC could be integrated with specific biblical ideas, its alignment with theological cosmology, and how it compares to other models.

CCC and Biblical Themes

Renewal of Creation

CCC’s Renewal Across Aeons:

- CCC describes the universe undergoing infinite cycles, with each aeon beginning anew after the previous one ends.

- This perpetual renewal echoes biblical themes of creation, destruction, and renewal. For instance:

Psalm 104:30: “When you send forth your Spirit, they are created, and you renew the face of the ground.”

Revelation 21:5: “Behold, I am making all things new.”

In CCC, each aeon is distinct yet linked to the previous one. This could be metaphorically tied to God’s ongoing work of sustaining and renewing creation.

Order from Chaos

Conformal Smoothness and the Initial State:

- In CCC, the universe transitions from the “chaos” of one aeon’s decay to the orderly beginning of the next aeon through the fine-tuned mechanism of conformal geometry.

- This reflects the biblical concept of God bringing order out of chaos:

Genesis 1:2: “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.”

God’s creative power to impose order on the cosmos parallels the finely tuned mechanisms in CCC.

Eternity and the Nature of Time

Infinite Aeons and Divine Eternity:

CCC proposes an infinite chain of aeons, with no ultimate beginning or end. While this differs from the biblical view of creation’s beginning (Genesis 1:1), it aligns with God’s eternal nature:

Psalm 90:2: “From everlasting to everlasting, you are God.”

The infinite nature of CCC’s aeons could metaphorically reflect the eternal, unchanging nature of God, who sustains creation across all time.

The Imprint of the Past

Hawking Points and Divine Imprints:

Penrose suggests that traces of previous aeons, such as Hawking Points in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), may persist into new cycles.

This idea resonates with biblical themes of God’s imprint on creation:

Romans 1:20: “For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.”

Just as Hawking Points serve as echoes of the past, creation itself bears the marks of its Creator.

CCC Compared to Other Theological Cosmologies

Standard Big Bang with a Creator

Biblical Alignment:

- The standard Big Bang model, with its singular origin, aligns closely with Genesis 1:1: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.”

- It reflects a finite creation event, emphasizing God’s sovereignty as the initiator of time, space, and matter.

Comparison with CCC:

CCC diverges by rejecting a singular beginning, instead proposing an eternal series of cycles. While this differs from the biblical narrative, it still reflects divine attributes of order, renewal, and eternity.

Steady-State Cosmology

Theological Challenges:

- The steady-state model assumes a universe with no beginning or end, in direct conflict with Genesis 1:1.

- It lacks renewal or fine-tuning mechanisms, making it less compatible with theological perspectives.

Comparison with CCC:

CCC, unlike the steady-state model, incorporates mechanisms for renewal and fine-tuning, aligning it more closely with theological ideas of a Creator’s sustaining power.

Multiverse Hypothesis

Theological Implications:

The multiverse posits infinite universes, each with different parameters. This attempts to explain fine-tuning without invoking a Creator.

However, it raises philosophical and theological questions, such as why such a multiverse exists at all.

Comparison with CCC:

CCC avoids the speculative complexity of the multiverse and focuses on one universe evolving cyclically. This simplicity is more consistent with the concept of a Creator establishing a single, orderly cosmos.

Theological Strengths of CCC

Fine-Tuning as Evidence for Design

CCC requires precise mechanisms, such as the vanishing of the Weyl curvature tensor and the conformal smoothness of spacetime, to ensure the transition between aeons.

The fine-tuning of these processes aligns with the idea of an intelligent Creator who designs the universe with purpose and precision.

Sustaining Creation

CCC reflects the ongoing sustenance of creation through cycles. This aligns with the biblical view of God as actively sustaining the universe:

Hebrews 1:3: “He upholds the universe by the word of his power.”

Purposeful Cyclicity

The cycles in CCC could reflect God’s intentional design for renewal and continuity in creation, mirroring theological concepts of restoration and hope.

Challenges of CCC from a Biblical Perspective

Infinite Cycles and the Beginning

The Bible emphasizes a finite beginning to creation (Genesis 1:1). CCC’s eternal cycles challenge this notion, suggesting an infinite past.

A potential reconciliation could involve interpreting CCC’s cycles as part of God’s sustaining work after the initial act of creation.

Lack of Eschatology

CCC does not include an ultimate culmination or end, as described in biblical eschatology (e.g., Revelation 21–22). Instead, it posits eternal recurrence.

Theologically, this could be seen as incomplete without acknowledging a final restoration and new creation.

Reconciling CCC with Biblical Creation

God’s Use of Cycles

CCC could represent a mechanism used by God within creation, much like other natural processes (e.g., the water cycle, ecological cycles). This view emphasizes God’s sovereignty over all mechanisms.

Creation’s Dependence on God

Even in CCC, the laws of physics and fine-tuning that govern the cycles point to a Creator who established and sustains these processes.

Eschatological Fulfillment

CCC could be understood as part of creation’s current state, with its cycles ultimately culminating in the eschatological fulfillment described in the Bible. The final renewal could represent the transition from temporal cycles to eternal perfection.

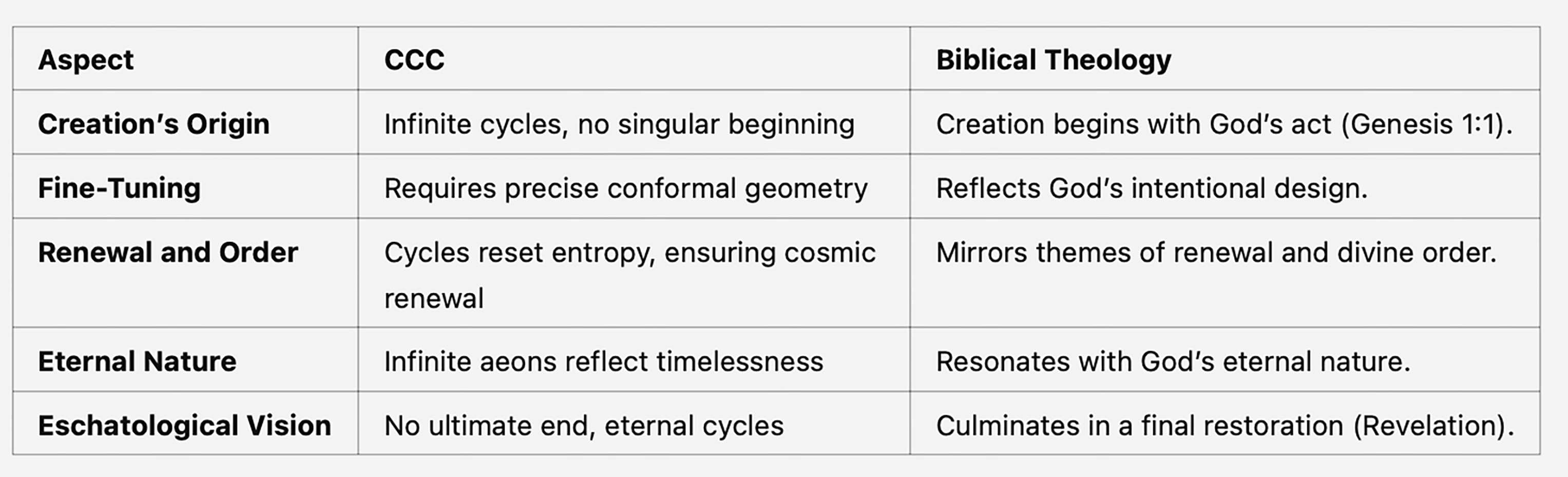

Aspect CCC Biblical Theology

- Creation’s Origin Infinite cycles, no singular beginning Creation begins with God’s act (Genesis 1:1).

- Fine-Tuning Requires precise conformal geometry Reflects God’s intentional design.

- Renewal and Order Cycles reset entropy, ensuring cosmic renewal Mirrors themes of renewal and divine order.

- Eternal Nature Infinite aeons reflect timelessness Resonates with God’s eternal nature.

- Eschatological Vision No ultimate end, eternal cycles Culminates in a final restoration (Revelation).

Exploring CCC’s Alignment with Eschatological Themes and a Creator’s Role

Roger Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) offers a framework for understanding the universe’s evolution through infinite cycles or “aeons.” While CCC is a naturalistic model, its principles can be evaluated in light of biblical eschatology and the role of a Creator. Below, we’ll delve into how CCC might align with theological themes of final restoration, divine renewal, and God’s ultimate purposes.

Eschatological Themes and CCC

Copyright, RCR

Copyright, RCRRenewal and the Cycle of Aeons

CCC’s Eternal Renewal:

In CCC, each aeon transitions into the next through conformal smoothness, representing a form of cosmic renewal. This perpetual renewal aligns with biblical themes of God restoring creation:

Isaiah 65:17: “For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered.”

Revelation 21:5: “Behold, I am making all things new.”

CCC could metaphorically reflect God’s sustaining power in maintaining and renewing the cosmos across time.

Theological Distinction:

CCC’s cycles are naturalistic and lack a culmination. Biblical eschatology, however, points to an ultimate renewal that is not part of an infinite process but a final state:

2 Peter 3:13: “But according to his promise we are waiting for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells.”

The transition from temporal cycles to an eternal new creation could represent the final aeon, in which God’s kingdom is fully realized.

The Role of Judgment and Restoration

Entropy and Judgment:

In CCC, the end of each aeon involves the decay of all matter into radiation, erasing the structures of the previous aeon. This echoes biblical themes of judgment and purification:

Isaiah 34:4: “All the host of heaven shall rot away, and the skies roll up like a scroll.”

2 Peter 3:10: “The heavens will pass away with a roar, and the heavenly bodies will be burned up and dissolved.”

CCC’s process of entropy resetting at the end of an aeon parallels the biblical idea of God purging creation in preparation for renewal.

Restoration in the New Aeon:

CCC’s conformal smoothness after entropy aligns with the biblical concept of restoration, where God re-creates a perfected universe:

Revelation 21:4: “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more.”

Reconciling CCC’s Infinite Cycles with Biblical Eschatology

A Creator’s Role in Sustaining Cycles

God as Sustainer:

CCC requires fine-tuning to ensure the transition between aeons. A Creator could be understood as the one who established these cycles and sustains their operation:

Colossians 1:17: “He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

CCC’s cycles could be seen as part of God’s providential care over creation, maintaining its existence through time.

The Final Aeon

Eternal New Creation:

While CCC posits infinite cycles, biblical eschatology points to a final aeon where God establishes an eternal new creation:

Revelation 22:3-5: “No longer will there be anything accursed, but the throne of God and of the Lamb will be in it, and his servants will worship him. They will reign forever and ever.”

This final state could represent the culmination of the cycles described in CCC, marking the transition from temporal renewal to eternal perfection.

Cosmic Culmination:

CCC’s infinite aeons could be understood as the “prelude” to God’s ultimate plan, where temporal cycles serve a purpose until the final restoration of all things:

Ephesians 1:10: “As a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.”

CCC and Theological Concepts of Time and Eternity

The Nature of Time

Temporal Cycles and Divine Eternity:

CCC’s infinite aeons reflect a cyclical view of time, which contrasts with the biblical view of time as linear, culminating in an eternal state.

However, God’s eternal nature could encompass both linear and cyclical time, with cycles serving as part of His temporal creation until the final fulfillment.

God as Creator of Time:

CCC assumes that time exists indefinitely through aeons, but theologically, God is the creator of time itself:

Genesis 1:1: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.”

A Creator who exists outside of time could design cycles for temporal purposes, ultimately transitioning creation into eternity.

The Imprint of Previous Aeons

Hawking Points and Divine Memory:

Penrose’s hypothesis that traces of previous aeons remain in the CMB echoes theological ideas of God’s memory of creation:

Malachi 3:16: “A book of remembrance was written before him of those who feared the Lord.”

Just as Hawking Points may preserve echoes of the past, God’s omniscience encompasses all events in creation, past and future.

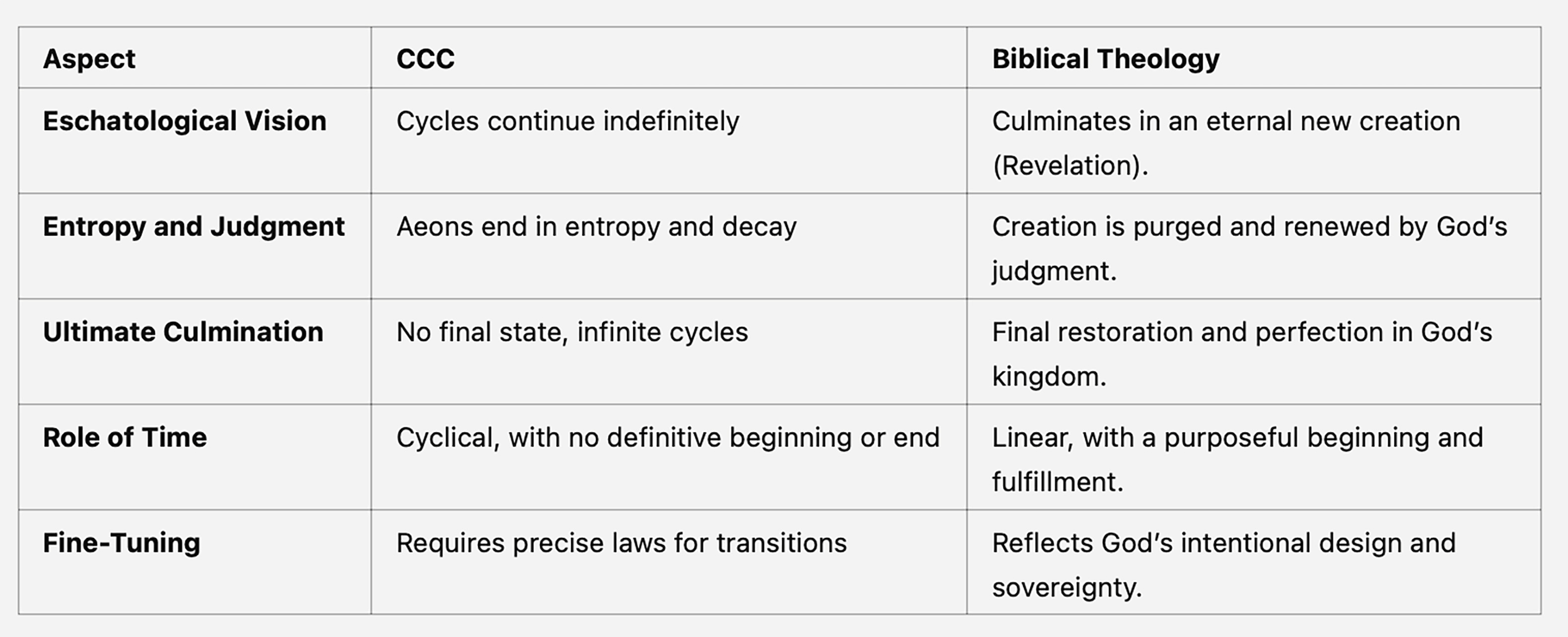

CCC vs. Theological Cosmological Models

Copyright, RCR

Copyright, RCRAspect CCC Biblical Theology

Eschatological Vision Cycles continue indefinitely Culminates in an eternal new creation (Revelation).

Entropy and Judgment Aeons end in entropy and decay Creation is purged and renewed by God’s judgment.

Ultimate Culmination No final state, infinite cycles Final restoration and perfection in God’s kingdom.

Role of Time Cyclical, with no definitive beginning or end Linear, with a purposeful beginning and fulfillment.

Fine-Tuning Requires precise laws for transitions Reflects God’s intentional design and sovereignty.

Theological Reflections on CCC’s Cycles

Cycles as Divine Providence

CCC’s eternal cycles could be interpreted as a manifestation of God’s providence, ensuring the continued existence of creation until His ultimate plan is fulfilled.

The Limitations of CCC

While CCC describes infinite renewal, it lacks a vision of ultimate purpose or culmination. Theologically, God’s plan for creation includes a final state of eternal harmony, which CCC does not address.

Cycles as Temporary

CCC’s cycles could serve as a temporary mechanism, preparing creation for its ultimate transformation into an eternal state. This aligns with the idea that creation is “groaning” and awaiting its final redemption:

Romans 8:22-23: “For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now.”

Roger Penrose’s CCC, while naturalistic, offers a cosmological framework that can metaphorically reflect biblical themes of renewal, divine order, and sustenance. However, CCC falls short of addressing the ultimate eschatological culmination described in Scripture. Theologically, CCC’s cycles could be seen as part of God’s temporary mechanism for sustaining creation until His plan for a new heaven and earth is realized.

See: “A Universe That Proves God: The True Source of the Cosmos,” by Robert Clifton Robinson, at Amazon, in Kindle eBook, Paperback, and Hardback editions:

Kindle eBook, Paperback, and Hardback Editions

Kindle eBook, Paperback, and Hardback EditionsNOTES:

The information about Sir Roger Penrose presented in this discussion is drawn from a combination of widely recognized sources, Penrose’s own writings, interviews, and public lectures. The following are the sources and citations for the key points discussed:

Primary Sources by Roger Penrose

Books:

- Penrose, R. (1989). The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. Oxford University Press.

- Penrose, R. (1994). Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness. Oxford University Press.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Vintage Books.

- Penrose, R. (2010). Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Penrose, R. (2016). Fashion, Faith, and Fantasy in the New Physics of the Universe. Princeton University Press.

Research Papers:

- Penrose, R. (1965). Gravitational collapse and space-time singularities. Physical Review Letters, 14(3), 57–59. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.57.

- Penrose, R. (1971). Twistor Algebra. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 12(1), 58–80.

Nobel Prize Lecture (2020):

- Available at NobelPrize.org.

Interviews and Public Lectures

Roger Penrose Public Lectures:

- YouTube hosts numerous public lectures where Penrose explains his theories in accessible language. Key examples include discussions hosted by the Perimeter Institute and Oxford University.

- Notable Lecture: “What We Need to Understand About the Universe” (Royal Society of Arts, 2016).

Interviews:

- “Roger Penrose: Why Consciousness Does Not Compute” (Scientific American, 2014).

- Interview on the nature of mathematics and reality in The Guardian (2011).

Secondary Sources and Commentaries

On Fine-Tuning and Cosmology:

- Barrow, J. D., & Tipler, F. J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford University Press.

- Ellis, G. F. R., Kirchner, U., & Stoeger, W. R. (2004). Multiverses and Physical Cosmology. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 347(3), 921–936.

On Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC):

- Commentary on Penrose’s CCC model in New Scientist (2010).

- Peer critiques and support for CCC in Nature Physics.

Penrose’s Comments on Philosophy and Religion

While Penrose does not directly address theological topics like Jesus Christ or New Testament eyewitness testimony, his philosophical stance is discussed in secondary sources:

Agnosticism and Mathematics:

- “Penrose on the Role of Mathematics in the Universe” (The New York Times, 2004).

- Polkinghorne, J. (1998). Belief in God in an Age of Science. Yale University Press.

Science and Religion:

- Ellis, G. F. R. (2014). Issues in the Philosophy of Cosmology. Handbook of the Philosophy of Science.

Categories: Robert Clifton Robinson

Wonderful post 🙏🎸

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article 🎸🌅

LikeLike

Excellent overview.

LikeLiked by 1 person