New Testament Scholar, Bart Ehrman, Has Written An Opinion Framed As a Question: Did New Testament Scribes Ever Make “Astoundingly Bad Errors”?

The Following Is A Textual-Critical Impeachment to Bart Ehrman

Bart Ehrman has repeatedly posed the question, *“Did scribes of the New Testament ever make astoundingly bad errors when making a copy?”*¹ The question is rhetorically effective, but it is methodologically imprecise and historically misleading. It presupposes a definition of “error” that is neither carefully delimited nor grounded in the actual data of the New Testament manuscript tradition. When examined through established principles of textual criticism and historical method, the question loses its force and fails to support the skeptical conclusions often implied by it.

This formal impeachment will demonstrate four points: (1) that scribal variation is a universal feature of all handwritten traditions and does not imply corruption; (2) that the New Testament manuscript tradition is uniquely transparent and well-attested; (3) that alleged “severe” scribal errors are rare, detectable, and theologically inconsequential; and (4) that Ehrman’s framing conflates the existence of variants with the loss of the original text—a category error rejected by mainstream textual criticism.

Scribal Variation and the Nature of Hand-Copied Texts

All ancient literature transmitted by hand exhibits scribal variants. This is not a peculiarity of the New Testament, nor is it evidence of instability. Classical texts such as Homer, Plato, Tacitus, and Josephus survive in far fewer manuscripts—often separated from their autographs by centuries—yet historians do not treat their textual variation as disqualifying their historical reliability.²

Textual criticism exists precisely because scribes were human. Common scribal phenomena include misspellings, transposed word order, dittography (accidental repetition), haplography (accidental omission), and minor stylistic smoothing.³ These are mechanical, not ideological, and they are easily identifiable when multiple manuscript witnesses are available.

The crucial issue, therefore, is not whether variants exist, but whether those variants prevent the recovery of the original text or introduce doctrinal corruption. On that point, the manuscript evidence is decisive.

The Scope and Quality of the New Testament Manuscript Tradition

The New Testament is preserved in over 24,000 extant manuscripts, including Greek papyri, uncials, minuscules, lectionaries, and early versions in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Ethiopic.⁴ The earliest Greek papyri—such as P52, P66, and P75—date from the early second century, placing them within living memory of the apostolic era.⁵

This abundance allows textual critics to identify scribal variants with exceptional precision. Ironically, the very reason critics can point to differences in wording is because the New Testament tradition is so well preserved. A poorly attested text would hide corruption; the New Testament exposes it.

Kurt and Barbara Aland summarize the matter succinctly:

“The text of the New Testament has been transmitted in thousands of witnesses, enabling us to reconstruct the original text with a very high degree of probability.”⁶

The Nature of Textual Variants

When the full manuscript corpus is examined, the data reveal that approximately 99% of all textual variants are trivial, involving spelling, word order, or stylistic differences that do not affect meaning.⁷ Less than 1% are meaningful, and only a fraction of those are viable (i.e., supported by more than one manuscript family).

No variant alters any core Christian doctrine or important fact about Jesus

This conclusion is not disputed by evangelical scholars alone. Bruce Metzger—Ehrman’s own doctoral advisor—affirmed:

“The great mass of the New Testament variants are insignificant… and no doctrine is affected by textual variants.”⁸

Ehrman himself has publicly acknowledged this point, despite often minimizing its significance in popular-level works.⁹

Alleged “Astoundingly Bad” Errors Examined

The few passages frequently cited as examples of serious scribal error do not bear the weight placed upon them.

Mark 1:41, for example, contains a variant in which Jesus is described as being “angry” rather than “compassionate.” The variant is early but rare, geographically limited, and immediately recognizable. Textual critics debate its originality precisely because the manuscript evidence allows them to do so.¹⁰ The passage does not introduce a new doctrine, nor does it obscure the narrative portrayal of Jesus across the Gospel tradition.

Mark 1:41 “Then Jesus, moved with compassion, stretched out His hand and touched him, and said to him, ‘I am willing; be cleansed.”

The word “compassion,” here in Mark 1:41, is from the Koine Greek, σπλαγχνίζομαι splagchnizomai.

Similarly, in the text of John 11:33-39, we find the usage of the English word “angry,” used to describe Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus. When Jesus saw the effects of death, suffering, and great despair for the family and friends of Lazarus, He was angry. Sin has destroyed human life on Earth. One of the reasons that Jesus came to earth was to end the misery and suffering of death. He accomplished this by dying for all sins and thereby removing the curse of death forever.

We might object to the usage of “angry” as applied to Jesus in this context, where we might imagine that the more correct word, compassion or sorrow, should be used. It is certain that Jesus felt sorrow and compassion, but as Yahweh, the Creator of human life on Earth, Jesus at that moment was also very angry at seeing the destruction death has wrought upon human life.

John 11:33-39 “When Jesus saw her weeping and saw the other people wailing with her, a deep anger welled up within him, and he was deeply troubled. 34 “Where have you put him?” he asked them. They told him, “Lord, come and see.” 35 Then Jesus wept. 36 The people who were standing nearby said, “See how much he loved him!” 37 But some said, “This man healed a blind man. Couldn’t he have kept Lazarus from dying?” 38 Jesus was still angry as he arrived at the tomb, a cave with a stone rolled across its entrance. 39 “Roll the stone aside,” Jesus told them.” (NLT)

The NKJV version writes something interesting for this text using the Koine Greek, ἐμβριμάομαι embrimaomai. “Angry”

John 11:38-39 Then Jesus, again groaning in Himself, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone lay against it. 39 Jesus said, “Take away the stone.”

Here, under similar circumstances, Jesus was again “angry,” as was translated in Mark 1:41 by one translation, where others wrote, “compassion.”

Therefore, the usage in Mark 1:41 is not at all out of context with what was taking place at that moment, and does not certainly change the meaning of the text that is in question. In fact, it may help the reader understand with more clarity that Jesus was angry, again, at what sin had caused in the context of Mark 1:41.

Similarly, the Pericope Adulterae (John 7:53–8:11) is absent from the earliest manuscripts and appears with scribal markings or relocation in later copies. Modern translations openly flag this passage. Far from being an example of deceptive corruption, it is one of the most transparently documented textual variants in all of antiquity.¹¹

In each case, the presence of variants demonstrates not chaos, but control.

A Category Error in Ehrman’s Framing

Ehrman’s question implicitly commits a category error by equating variation with corruption. These are not synonymous. Variation is inevitable in hand-copied texts; corruption would require that the original wording be irretrievable or doctrinally altered. The New Testament meets neither criterion.

Daniel Wallace correctly observes:

“The reason we have so many variants is because we have so many manuscripts. The more manuscripts we discover, the more variants we find—but also the more confident we become about the original text.”¹²

This is standard textual-critical reasoning, not theological special pleading.

Doctrinal Stability Across Manuscript Families

Perhaps the most decisive evidence against the claim of “astoundingly bad” errors is doctrinal consistency across independent manuscript traditions. Long before any centralized ecclesiastical authority existed to enforce uniformity, New Testament texts circulated across the Roman world—in Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Yet doctrines such as the deity of Christ, the resurrection, salvation by grace, and the crucifixion appear consistently across geographically diverse witnesses.¹³ This level of coherence is inexplicable if scribal corruption were rampant or ideologically driven.

Did New Testament scribes ever make mistakes? Yes—because they were human.

Did they make errors that destroyed the text, altered doctrine, or rendered the New Testament historically unreliable? No.

Ehrman’s question trades on ambiguity rather than evidence. When subjected to the full manuscript data and the accepted principles of textual criticism, the New Testament emerges not as a cautionary tale of corruption, but as the most textually secure body of literature from the ancient world.

The real historical conclusion is not that the New Testament was corrupted beyond recovery, but that it has been preserved with extraordinary fidelity—openly, transparently, and verifiably.

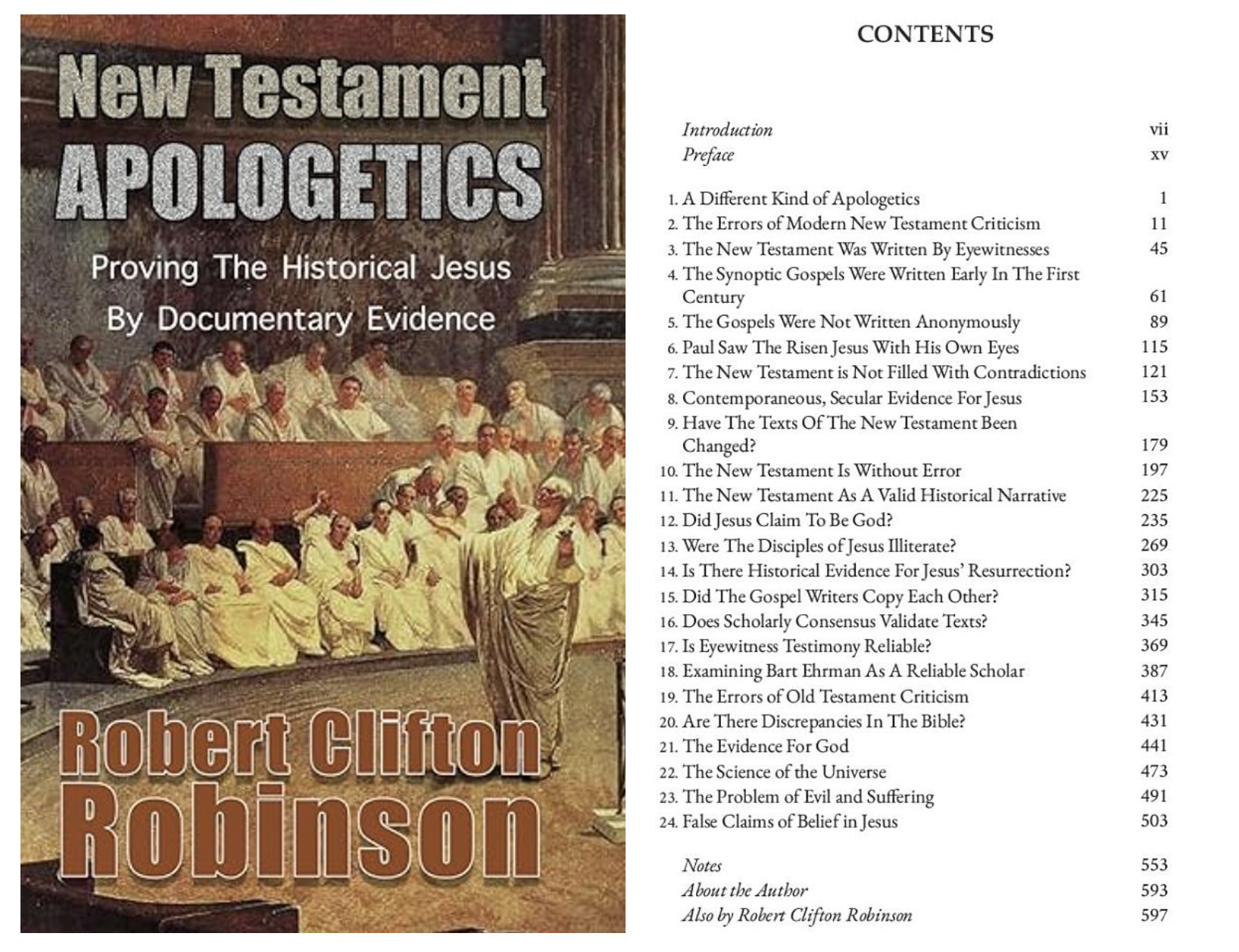

See Rob’s Publication That Impeaches Many of the False Assertions Made by Bart Ehrman Regarding Textual Reliability of the New Testament: “New Testament Apologetics“

Sources and Citations:

- Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus (New York: HarperOne, 2005), 7–9.

- F. F. Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 15–33.

- Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012), 222–235.

- Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 82–85.

- Philip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2005), 58–70.

- Aland and Aland, Text of the New Testament, 287.

- Daniel B. Wallace, “The Majority Text and the Original Text,” Bibliotheca Sacra 136 (1979): 25–26.

- Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 251.

- Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 220.

- Metzger, Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1994), 65.

- Wallace, “Reconsidering ‘The Story of the Woman Taken in Adultery,’” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 39 (1996): 290–296.

- Daniel B. Wallace, “Why So Many Manuscripts?” Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts.

- Simon Greenleaf, The Testimony of the Evangelists (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1984), 22–35.

Categories: Robert Clifton Robinson

Please see, "Guidelines For Debate," at the right-side menu. Post your comment or argument here: