It Is Easy To Assert New Testament Unreliability; It Is Another Matter To Prove New Testament Unreliability; It Cannot Be Done.

Let’s examine what Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976) and Bart Ehrman (b.1955) have actually argued, and what they present as “evidence” for the claim that the Gospels arose from a long oral tradition that was distorted over time. More importantly, the fact that what they present as proof that the New Testament is not reliable are theories and interpretations consisting of form and redaction criticism, not precise, manuscript-based evidence.

Rudolf Bultmann (Form Criticism and Oral Tradition)

Bultmann’s Primary Assertions:

- The Gospels are “folklore-like collections” of units (pericopes) transmitted orally in the early Christian communities before being written.

- The stories about Jesus (miracles, parables, controversies) were shaped by the needs of the early church (“Sitz im Leben der Kirche” = “setting in life of the church”), not by historical accuracy.

- Much of what the Gospels record is mythological expressions of faith, not literal history.

The Evidence Bultmann Appeals To

Form criticism: He analyzes the literary “forms” of Gospel pericopes (miracle story, pronouncement story, legend, etc.) and concludes they resemble oral folklore genres.

Rudolf Bultmann’s publication: “History of the Synoptic Tradition (New York: Harper & Row, 1963 [German 1921]), esp. pp. 1–37. Bultmann points to differences between Synoptic parallels (e.g., how Mark, Matthew, and Luke report the same story with minor changes) as proof that they developed these narratives by oral retellings. Evidence: The differences in the wording of Peter’s confession (Matt 16:16 vs. Mark 8:29 vs. Luke 9:20).

Bultmann assumes that sayings attributed to Jesus often reflect later church debates rather than authentic words of Jesus. Disputes about Sabbath (Mark 2:27) are explained as reflecting first-century church conflicts, not actual events with Jesus.

The problem with Bultmann’s “evidence” is that it is not documentary but interpretive — he assumes variation = distortion, and that theological development = invention. He did not have earlier manuscripts to prove his theory.

Bart Ehrman (Oral Transmission & Corruption)

Ehrman’s Primary Assertions: The Gospels reflect decades of oral transmission (30–65 years after Jesus’ death). Oral traditions in antiquity, like in modern memory experiments, were fluid, prone to change, and thus produced distorted accounts. By the time the evangelists wrote, the stories about Jesus had been reshaped in different communities to meet their needs.

Evidence Ehrman Appeals To:

Dating assumptions: Eherman adopts late dating (Mark ~70 AD; Matthew/Luke ~80–85 AD; John ~90–95 AD). This is a gap of at least 40–65 years after Jesus died and rose from the dead. Bart D. Ehrman, “Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 42–47.

Variations in manuscript tradition: Ehrman cites thousands of textual variants among the New Testament manuscripts as evidence of “fluidity” and “corruption.” Ehrman’s book, “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why” (New York: HarperOne, 2005), chs. 1–2.

Ehrman compares the Gospel transmission to anthropological studies of oral cultures where storytellers alter details for context, arguing the same occurred with Jesus’ traditions. Ehrman, “Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior” (New York: HarperOne, 2016), esp. pp. 45–90. Like Bultmann, Ehrman highlights contradictions in parallel Gospel accounts (e.g., Jairus’ daughter—dead before Jesus arrives in Matthew 9:18 vs. still alive in Mark 5:23) as proof that stories were reshaped orally.

The problem for Bart Ehrman is that his “evidence” depends on late dating assumptions and modern memory theory, but he admits there is no extant documentary trail of oral stages before the Gospels. The earliest papyri (P52, P46, P66, P75) have proven that stable texts already existed for the New Testament within 100–150 years of the events.

A Critical Assessment of Bultmann and Ehrman’s “Evidence”

Neither Bultmann nor Ehrman can point to actual 1st-century oral transcripts or fragments. Their argument is inference-based:

- The Gospels were written “late.”

- Oral transmission is unstable.

- Therefore, the Gospels = distorted oral tradition.

Modern papyrological evidence (NT papyri from 175–225 AD) impeaches the idea of long uncontrolled oral development, since the textual tradition is already widespread and stable by then. In fact, memory studies now show that oral societies often preserve core information with remarkable accuracy (see Kenneth Bailey, Informal Controlled Oral Tradition, 1991).

Bultmann: argued from form criticism, claiming Gospel pericopes (clear beginning and end) are folklore-like stories created and reshaped by the early church.

Ehrman argues from late dating, memory distortion studies, and textual variants, claiming oral transmission introduced distortion before the Gospels were written.

Neither of the views of these two men presents manuscript evidence that proves their false assertions—their case rests on theoretical reconstructions and presuppositions about late dating and oral unreliability.

In other words, there is no real evidence that the late-date writing of the Gospel assertions is actually true.

The opinions of Bultmann and Ehrman are based upon unprovable, undocumented guesswork. This demonstrates that the agenda and bias of Bultmann and Ehrman are to try and disprove the reliability of the Gospel narratives, not to prove by any scholarly evidence that these texts were written long after the men who saw Jesus actually wrote their narratives. The reason these two men do not present any evidence is that no evidence exists. They must resort to presumptions and distortions to make their readers believe the New Testament is not reliable.

Either the New Testament is true or it is not.

If we can believe by all that we see, that God is the only logical, practical, and sufficient source for the universe, then all of the miracles and other supernatural events described by the Bible are easy to accept. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” If we can believe this first statement that is made in the first sentence of the first book of the Bible, then a talking donkey, a global flood, a long day of Joshua, and the tens of thousands that Jesus healed, then all of these supernatural events in the Bible are very easy to accept as true.

Either all of the Bible is true or none of it is true. Since God had the power to speak the universe into existence (Psalms 33:6), He has the power to speak to select men who set apart their lives for Him, to record what God wants the world to know about Him. He also has the power to preserve exactly what He wants us to know through every generation.

The texts of the Bible we have today are exactly what God wants us to have. No person has had the power to change or corrupt what God wanted recorded for every generation of people to read and understand about God. It is interesting that once we understand this simple truth, everything else concerning the Bible becomes very easy to accept as true.

Bultmann and Ehrman do not believe God exists, that the Bible is His Word, or that the events of supernatural origin described in the Bible are possible in a naturalistic world. I just happened to know that this world we live in, this universe our planet is placed into, could not exist by a natural process. In my book “A Universe That Proves God: The True Source of the Cosmos,” I present the scientific evidence that proves only an unlimited Being is capable of creating a complex and well-ordered universe that exists by 209 fine-tuned physical constants.

The same God who created the universe created His word in a book that consists of 66 chapters, written by 40 authors, over a 1,450-year period of time. Everything that is in the Bible is true, and there has never been any proof at any time that proves any part of the Bible is not true. I have challenged thousands of people to provide this evidence that anything in the Bible is not true, and not one has been able to accomplish this simple request.

The Bible is true, and it comes to us, perfect, exactly as God wanted us to see it and understand who He is. We don’t need human critical theory to examine and scrutinize the Bible by deceitful and erroneously crafted procedures. These critical methods do not help anyone to know and understand what the Bible teaches or who God is. These critical assertions are crafted for the express purpose of destroying faith in God and His word, and many there are who have been deceived by these devious assertions.

If anyone simply reads and examines the testimonies about Jesus in the New Testament, it quickly becomes clear that these are not fabricated stories, but eyewitness historical narratives of true events. This is the path I took in 1975, when, as an atheist, I read through the New Testament for the first time. I have been a believer in the truth of all the Bible for more than 50 years, and not once have I ever, in all my personal scholarship, found anything that has rendered the Bible untrue or unreliable by evidence.

What Bultmann and Ehrman Fail To Prove:

- Claims of late dating and oral distortion are not based on physical, documentary evidence (no manuscripts, no contemporaneous testimony).

- Bultmann and Ehrman rely on unprovable assumptions about dating (e.g., “the Gospels must be post-70 AD because Jesus predicts the fall of Jerusalem,” which is a presupposition against prophecy, not an evidence-based conclusion).

- Both assert Literary theories (form criticism, redaction criticism).

- Both assert Sociological models of oral tradition.

- Neither can prove their assertions about the New Testament being unreliable by actual evidence. All of their conclusions are predicated upon their feeling and opinions. Both expect their readers to trust them because they are known as “New Testament Scholars.”

These claims, the Bultmann and Ehrman state, produce only conjecture and speculation, no proofs. No papyrus, codex, inscription, or ancient testimony has ever been uncovered proving that the Gospels were written late in the first century or into the 2nd century.

What the Extant Historical Evidence Actually Proves:

- By 175–225 AD, we already have most of the NT in papyri (P45, 46, 66, P75).

- Since papyrus normally survives 150–200 years, these must descend from autographs or copies written far earlier, in the mid-1st century.

- The early church fathers (Papias, Irenaeus, Justin Martyr) cite or allude to the Gospels long before 175 AD:

- Papias (c. 110 AD) testifies to Matthew and Mark.

- Irenaeus (c. 180 AD) affirms the four Gospels as authoritative.

- This points strongly to early, stable, recognized Gospels, not late, evolving oral folklore.

Bias and Agenda

Bultmann worked within the liberal German theological project of “demythologizing” the New Testament. His goal was to strip supernatural claims from the text and re-interpret Christianity in existential terms. He began with the assumption that miracles and prophecy cannot be historical.

Ehrman emphasizes contradictions, corruption, and uncertainty in order to argue that the New Testament cannot be fully trusted as the “Word of God.” The problem for Ehrman is that there are no contradictions according to the classific definition of a genuine contradiction: when two things cannot be true at the same time. In the case of the Synoptic Gospels, multiple eyewitnesses testify to the same events that concern Jesus, but each independent witness remembers different details. These are not contradictory, but additional to the others. This also serves as evidence of truthful, independent sources.

Ehrman admits in his book “Misquoting Jesus” that he began as an evangelical and shifted because of his prior commitment to agnostic/atheistic presuppositions.

Neither Bultmann nor Ehram approaches the New Testament as eyewitness historical testimony, which clearly it was written as; they approach these texts as suspect religious literature. This is due to their cognitive bias, not because of evidence.

The result: The “late dating” assertions of Bultmann and Ehrman are not conclusions based upon manuscript evidence, but expressions of their preconceived worldview — an anti-supernatural bias (Bultmann) and a skepticism of inspiration/reliability (Ehrman).

Question Answered

- There is no real evidence that the Gospels were written late in the first century.

- Claims that the writers never knew Jesus and wrote late into the first century have no provable documentation.

- Does this show an agenda/bias? Yes. The methods used by Bultmann and Ehrman start with the assumption that prophecy, miracles, and eyewitness authority cannot be true; therefore, they must be explained as later fabrications.

The late-date hypothesis is not proven by evidence but driven by presuppositions:

- Since prophecy is impossible → the Gospels must be after 70 AD.

- Since miracles are impossible → miracle stories must be fabricated myths.

- Since eyewitnesses are unreliable → the narratives must be decades later.

This is circular reasoning, not documentary proof.

The extant evidence of the New Testament manuscripts (early papyri, patristic citations, manuscript survival windows) actually proves very early Gospel writing, fully compatible with the 44–45 AD thesis.

Were the Gospels “Late” Products of a Long, Distorting Oral Process? A Documented Rebuttal

The two most frequently cited late-dating/oral-distortion accounts—Rudolf Bultmann’s form-critical reconstruction and Bart D. Ehrman’s memory/textual-fluidity model—rest primarily on theoretical and methodological premises rather than on documentary evidence. When weighed against early patristic testimony and the manuscript record, their conclusions are at best conjectural and at worst circular.

Rudolf Bultmann: Form Criticism as Presupposition

Bultmann argued that the Gospels comprise small, originally independent oral “forms” (pericopes) shaped by church needs (Sitz im Leben), and that historical knowledge of Jesus is minimal. In his oft-quoted line: “We can now know almost nothing concerning the life and personality of Jesus.” (He bases this skepticism on his reading of the sources as fragmentary, legendary, and theologically motivated.)

The Impeachment

The extant New Testament manuscripts we have in our possession, 24,593 documents, present a vast knowledge of Jesus. His life, ministry of healing tens of thousands of people (“everyone brought to Him”), and eye witness testimony (203 eyewitness statements), prove that we have a tremendous reservoir of reliable, historical, eyewitness testimony about Jesus.

What Bultmann offers is not early documentation but an interpretive tactic: to classify literary forms → infer community settings → posit oral reshaping. Contemporary summaries of form-critical presuppositions make it clear that this approach assumes anonymous, accretive oral transmission before written Gospels.

We don’t have to assume anything in simply reading the New Testament narratives about Jesus. These texts are detailed in providing us with the facts that men who had “been with Jesus since the beginning of His ministry” recorded the events they saw with their own eyes. These men specifically say they saw Jesus with their own eyes, including Paul.

These men state repeatedly that they saw and heard Jesus, and there is no ambiguity in what they meant:

- Paul: 1 Corinthians 9:1: “Am I not an apostle? Haven’t I seen Jesus our Lord with my own eyes?

- Peter: 1 Peter 1:16: “We saw his majestic splendor with our own eyes.”

- John: 1 John 1:1: “We saw him with our own eyes and touched him with our own hands.”

- James, Paul, all the Apostles: 1 Corinthians 15:7: “Then Jesus was seen alive by James and later by all the apostles. Last of all, as though I had been born at the wrong time, I also saw him.”

- Mary Magdalene: John 20:18: “Mary Magdalene found the disciples and told them, ‘I have seen the Lord!”

- Peter: Acts 5:29-32: “But Peter and the apostles replied… We are witnesses of these things…”

- John: 1 John 1:2-3: “This one who is life itself was revealed to us, and we have seen him. And now we testify and proclaim to you that he is the one who is eternal life. He was with the Father, and then he was revealed to us. We proclaim to you what we ourselves have actually seen and heard so that you may have fellowship with us.

You can find a list of all 203 of these eyewitness statements found in the New Testament in an essay located on my website at the link provided in this sentence.

A representative statement (quoted via Bailey, who cites Jesus and the Word): “What the sources offer us is first of all, the message of the early Christian community, which … the Church freely attributed to Jesus.”

Bultmann’s reconstruction of the Gospel texts is method-driven (literary forms + assumed Sitz im Leben), not document-driven. In other words, Bultmann fabricated a method by his own hand that allows him to convince people as a scholar that the Gospels are not true. Rather than use the simple procedure accessed in the determination of all historical documents, to read the texts, study the texts, and learn what they say, Bultmann interposes his own methods that he created to try and discredit the New Testament texts. It doesn’t work. Anyone who simply reads the texts for themselves can quickly see that they are compelling eyewitness testimony of men who saw what they recorded.

Bart D. Ehrman: Memory, Variants, and a Long Gap

Ehrman contends the Gospels were written decades after Jesus, reflecting fluid oral memories and scribal alterations. The problem for Ehrman is that the actual texts of the New Testament impeach all of his assertions. It is clear to any reader of the Gospel narratives that these accounts were written by men who were there when these things happened. They tell us with their own words that they “saw Jesus, heard Him,” and “wrote these things so that we will know the truth concerning Jesus.”

Typical Ehrman encapsulations include: “There are more variations among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament,” and “We don’t have any originals … Our copies are later generation copies.”

When we examine the actual “variations” that Ehrman asserts, we find that if one word is misspelled a thousand times, though it is the same word, it is counted as a thousand variants. A most disingenuous method.

In Ehrman’s book, “Jesus Before the Gospels,” he frames the project as one about “memory, and distorted memory.” Ehrman points to (a) late dates commonly adopted in critical introductions, (b) well-known textual variants (e.g., Mark 16:9–20; John 7:53–8:11), and (c) modern memory research analogies. But none of these provides a documentary chain of oral stages prior to the Gospels. The textual-variant argument describes copying after writing began, not oral development before writing.

Ehrman’s model depends on (1) adopting later dates as a premise and (2) extrapolating from general memory studies to first-century Christian communities. In other words, Ehrman fabricates methods that will prove his false assertions, which are unprovable. The later date is not provable, but when Ehrman states numerous times in his publications that the Synoptic Gospels were written late in the first century by men who never saw Jesus, people who read his books believe him because he is known as a New Testament scholar. Even PhDs must prove their suppositions. Ehrman cannot prove a late-date writing; he merely asserts it as true because this satisfies his own prejudice against the accuracy and miracles recorded by the men who saw and heard Jesus.

In none of his books does Ehrman ever provide the reader with primary evidence that the Jesus traditions were, in fact, long, uncontrolled, and distorted before inscription.

Positive, Documentary Counter-Impeachments

Early patristic testimony to Gospel origins

- Papias via Eusebius (c. 120–140 CE): “Mark, having become the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatsoever he remembered …”

Also, “Matthew wrote the oracles in the Hebrew language …” Both of these citations are explicit claims of authorship linked to eyewitness sources.

- Irenaeus (c. 180 CE): the Gospel was first preached publicly and “at a later period … handed down to us in the Scriptures.” The context presupposes a fourfold Gospel already authoritative.

These are early, positive, external testimonies contradicting the notion of anonymous, late-date writing by men who never saw Jesus.

The papyrological horizon: substantial NT text by the late second/early third century

- P46 (Paul/Hebrews): palaeographically c. 175–225 (or early 3rd c.).

- P66 (John): traditionally early 3rd / c. 200, very close to P75/Vaticanus text.

- P75 (Luke–John): traditionally 3rd century (some studies argue early 4th), with a remarkably stable text relative to Codex Vaticanus.

Even allowing for time, the finality is certain: by ~200 CE, a wide usage of the New Testament exists in codices reflecting a comparatively conservative text. This is hard to reconcile with a preceding century of uncontrolled, distorting oral flux. Standard handbooks (Metzger–Ehrman; Aland & Aland) synthesize this evidence.

Eyewitness-model alternatives

Although the surviving manuscript evidence presents us with substantial proof that all of the narratives about Jesus that are recorded were through men who saw Jesus, Richard Bauckham argues the Gospels “are much closer to the form in which the eyewitnesses told their stories … the Evangelists were in more or less direct contact with eyewitnesses.”

If we understand the nature of Luke’s Gospel, which states: (Luke 1:1-4) “Many people have set out to write accounts about the events that have been fulfilled among us. They used the eyewitness reports circulating among us from the early disciples. Having carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I also have decided to write an accurate account for you, most honorable Theophilus, so you can be certain of the truth of everything you were taught.” We see the premise upon which he recorded his testimony.

Luke makes it clear that he personally interviewed all of the eyewitnesses who had been with Jesus since the beginning of His ministry, as a historian, an one who was determined to write the truth concerning Jesus.

Kenneth Bailey, drawing on Middle Eastern fieldwork, describes “informal controlled oral tradition,” a community-regulated mode that preserves a “relatively inflexible central core of information” while allowing limited variation. This specifically challenges Bultmann’s premise of uncontrolled oral processes.

Methodological Note: Circularity vs. Data

Bultmann: begins by denying access to Jesus’ life (“we can know almost nothing”), then reads the Gospels through a lens that predicts legendary accretion—an outcome his method virtually guarantees. This, again, in spite of the fact that the four Gospels tell us a great deal about Jesus, His life, death, and resurrection. There is greater information about Jesus in the historical record than about any other person of antiquity.

Ehrman: highlights manuscript variation (a copying phenomenon) and general memory fallibility to infer earlier oral distortion, without primary documentation of such distortion before the Gospels. He asserts his opinion over the facts of the New Testament, superimposing theories that are unprovable and only true in his own mind.

By contrast, patristic witnesses (early church) and the papyri (extant manuscripts) are hard data. These two historical sources indicate recognized, authored Gospels grounded in eyewitness testimony (Papias/Irenaeus) and a substantial, stable textual footprint by ~200 CE (P46/P66/P75).

There is no documentary proof that the canonical Gospels are late, anonymous folklore produced after a long period of distorting oral transmission. That thesis is a model, not a manuscript-based finding. The earliest external testimonies and the actual papyri point instead to early composition, stable transmission, and proximity to eyewitness memory—precisely the opposite of what Bultmann and Ehrman’s theories presuppose.

In the following, I provide an assertion by Bultmann and Ehrman, followed by an impeachment dossier for each false assertion.

I’ll take the assertion as given, then show how it collapses under the actual eyewitness and manuscript evidence we do have.

Rudolf Bultmann:

Quote: “We can now know almost nothing concerning the life and personality of Jesus …” (Jesus and the Word, 1958).

Impeachment: This is a sweeping assertion of ignorance, not an argument. By the time Bultmann wrote, scholars already had the full witness of the four Gospels, multiple Pauline letters (undisputed even by skeptics), and abundant extra-biblical testimony (Josephus, Tacitus, Pliny). Each contains specific, verifiable historical data about Jesus’ life, personality, and actions. To claim “almost nothing” can be known is not a conclusion of evidence, but a presupposition that discounts evidence because it records miracles and fulfilled prophecy. The New Testament, however, is written in the style of historical biography, filled with verifiable geographic, cultural, and political markers (Luke 3:1–2; John 5:2), not myth.

Bultmann (via Bailey):

Quote: “What the sources offer us is … the message of the early Christian community … freely attributed to Jesus.”

Impeachment: This assumes the early church invented sayings and retroactively ascribed them to Jesus. But both Luke and John explicitly claim the opposite:

- Luke 1:1–4: “they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses.”

- John 21:24: “This is the disciple who testifies … and we know his testimony is true.”

These are claims of direct eyewitness preservation, not “free invention.” Furthermore, Paul (1 Cor. 15:3–7) cites a resurrection creed already established within a few years of the crucifixion. That is not the invention of a later church, but an early fixed tradition.

Bart Ehrman:

Quote: “There are more variations among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament.”

Impeachment: This is a statistical trick. Yes, there are hundreds of thousands of textual variants — but they come from 5,800+ Greek manuscripts, with millions of copied words. Most “variants” are spelling differences or word order changes that have no effect on meaning. Less than 1% are both viable and meaningful, and not a single Christian doctrine depends on a disputed text (Metzger & Ehrman, Text of the NT, 4th ed., p. 252). The abundance of variants is actually proof of textual richness and transparency: we can compare manuscripts and reconstruct the original with a higher degree of confidence than for any other ancient text.

Bart Ehrman:

Quote: “We don’t have any originals … Our copies are later generation copies.”

Impeachment: This is true in a trivial sense — no autographs of any ancient text, secular or religious survive the first century. Yet the NT has far superior manuscript attestation than Homer, Plato, Tacitus, or Caesar’s Gallic Wars. Homer’s Iliad is preserved in ~650 manuscripts, with a 500-year gap from the originals; Tacitus’ Annals survive in just two medieval manuscripts, 800 years later. By contrast, the NT has thousands of manuscripts, some within 100 years of composition (P52, P46, P66). Ehrman’s statement is technically correct but misleading — the NT is the best-attested literature of antiquity.

Papias via Eusebius:

Quote: “Mark … wrote down accurately, though not in order …” (H.E. 3.39.15).

Impeachment: This is often seized on to imply that Mark was unreliable. But Papias actually affirms accuracy while acknowledging a difference in chronological order. In Greco-Roman biography, strict chronology was not required (see Plutarch, Suetonius). Mark’s concern is thematic arrangement, not error. Papias, an early witness (c. 110–130 AD), strengthens the case for Mark’s direct reliance on Peter’s eyewitness testimony.

Papias via Eusebius:

Quote: “Matthew wrote the oracles in the Hebrew language …” (H.E. 3.39.16).

Impeachment: This confirms that Matthew was regarded in the early 2nd century as the author of a Gospel source. Whether Papias means Hebrew or Aramaic, the key point is that Matthew’s Gospel was considered apostolic and rooted in a Jewish context. Far from suggesting late fabrication, Papias shows that the Gospel of Matthew was circulating early, in a Semitic form, within the living memory of the apostles.

Irenaeus:

Quote: “at a later period … handed down to us in the Scriptures …” (Against Heresies 3.1.1).

Impeachment: Irenaeus (c. 180 AD) insists that the Gospel he received was the same message first preached orally, and then written in the four Gospels. He explicitly names Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — the fourfold Gospel already fixed and authoritative in his time. This contradicts the claim that the canon was fluid or that the traditions were late. Instead, by 180 AD, the four Gospels were so widely accepted that Irenaeus appeals to them as exclusive, authoritative Scripture.

Richard Bauckham:

Quote: Gospels are “much closer to the form in which the eyewitnesses told their stories …”

Impeachment: Far from undermining reliability, this affirms it. Bauckham’s work (Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 2006) demonstrates that names, locations, and narrative features in the Gospels reflect first-century Palestinian context with remarkable accuracy. Statistical studies of personal names (Tal Ilan’s lexicon) show that Gospel name frequencies match exactly with Judea/Palestine in the 1st century — something impossible for later forgers in Greece or Rome. Bauckham’s conclusion undermines Bultmann and Ehrman: the Gospels are rooted in eyewitness recollection, not in long oral distortion.

Kenneth Bailey:

Quote: “informal controlled oral tradition … [with] a relatively inflexible central core of information.”

Impeachment: Bailey’s Middle Eastern fieldwork shows how oral societies preserve core details with remarkable fidelity, even as peripheral elements vary. Applied to the Gospels, this model demonstrates that the essentials of Jesus’ teaching, miracles, death, and resurrection would have been carefully safeguarded within the community. This is the opposite of Bultmann’s “free invention.” Bailey’s findings provide anthropological evidence that oral transmission of Jesus traditions was reliable, not myth-making.

- Bultmann’s assertions rest on presuppositions against the supernatural, not evidence.

- Ehrman’s arguments are technically true in part, but framed to exaggerate doubt while ignoring the NT’s unparalleled textual evidence.

- Patristic witnesses (Papias, Irenaeus) affirm authorship, accuracy, and early acceptance.

- Modern scholarship (Bauckham, Bailey) confirms that the Gospels are close to eyewitness testimony and transmitted reliably.

For these reasons, the late-date/oral-distortion theory is not an evidence-based conclusion but a bias-driven hypothesis. The actual eyewitness and manuscript record supports early, reliable, and historically anchored Gospel accounts.

“Synoptic Problem” or Synoptic Harmony?

The so-called “Synoptic Problem” exists only if we begin with the critical presupposition that the Gospels are not straightforward, historically reliable, eyewitness testimony.

What Scholars Mean by “the Synoptic Problem” The term refers to the assertion that critics make where they see the close similarities of the Synoptic Gospels as a problem. Critical scholars assert and assume that this similarity requires an explanation of literary dependence:

- Was Mark first, and Matthew and Luke used him? (Markan priority).

- Did Matthew come first? (Matthean priority).

- Was there a lost sayings source “Q”?

This “problem” is only a problem if a person denies that independent eyewitnesses could produce congruent testimony about shared events. The important fact of the Synoptic Gospels is that they display this very thing: all three are separate, independent, eyewitness testimonies that do not need to be reconciled by a fabricated and unnecessary process.

The Eyewitness Answer

If we take the Gospels as the historical testimony of men who saw and heard Jesus (Matthew, John) or wrote down the testimony of eyewitnesses (Mark from Peter, Luke from many sources: Luke 1:1-4), then agreement is produced naturally: the same events were seen and remembered by different people.

Variation arises naturally: eyewitnesses emphasize different details, just as happens in courtroom testimony. Overlaps in wording define the actual words of Jesus as carefully recorded by all three authors, because they wanted the words of Jesus to be known precisely.

In this model, the “Synoptic Problem” dissolves into a Synoptic Harmony: three complementary witnesses telling the same story.

The Synoptic Problem – Robert Clifton Robinson

The Historical Evidence for Eyewitness Testimony

Papias (c. 110–130 AD): “Mark … wrote down accurately whatever he remembered of the things said and done by the Lord … not, however, in order.”

“Matthew compiled the oracles in the Hebrew language, and each interpreted them as best he could.” These are explicit claims of apostolic or near-apostolic testimony.

Irenaeus (c. 180 AD): affirms the four Gospels as authoritative, grounded in apostolic witness (Against Heresies 3.1.1). Luke’s prologue claims careful investigation from “those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses” (Luke 1:2).

From the start, the Gospels were understood as eyewitness or close-to-eyewitness records, not anonymous patchworks.

Why “the Synoptic Problem” Persists in Critical Circles

Critics and people who do not believe God exists had to create a model that would allow them to deny that the Bible is a transcendent communication by an Eternal Being. For this reason, denying the source is God, the source must be natural. This requires an answer as to why the testimonies in the Synoptic Gospels are similar yet different. Of course, the easiest method (Occam) is to just accept that the Synoptics exist naturally in this form because they are written as they really took place.

Critics do not believe Jesus is Yahweh, the Eternal God, so when He predicted events in the Gospels that had not happened, the writers must have recorded the predictions after the events took place. Concerning Jesus’ prediction describing the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in precise detail, no fulfillment of this event is recorded in the Gospels, because these events had not happened. This stands as literary, historical evidence that the predictions of Jesus were written around 32 AD, just before He was crucified and rose from the dead.

Critics do not believe Jesus is Yahweh, the Eternal God, so when He predicted events in the Gospels that had not happened, the writers must have recorded the predictions after the events took place. Concerning Jesus’ prediction describing the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in precise detail, no fulfillment of this event is recorded in the Gospels, because these events had not happened. This stands as literary, historical evidence that the predictions of Jesus were written around 32 AD, just before He was crucified and rose from the dead.

The miracles of Jesus existed in the tens of thousands during the three and a half years of His public ministry. The Gospels record that “everyone who was brought to Jesus, He healed them all.” The Gospels record that large crowds in the tens of thousands were often gathered to hear Jesus. This defines Jesus as no normal man, but possessing the power that only the Eternal God, Yahweh, had demonstrated in the Old Testament.

Critics who do not accept the eyewitness historical testimony of the men who penned the New Testament had to fabricate an answer for why Jesus had the power to heal everyone brought to Him. The answer is to presuppose that no miracles happened because miracles are not possible, and Jesus did not have the power to heal. In order to assert this idea, a person would have to believe that the writers of the New Testament were lying and made up their testimony that says Jesus healed everyone who was brought to Him.

The historical extant manuscript copies of the New Testament stand as evidence that proves men saw Jesus do the things recorded in the Gospels. The Old Testament (Isaiah 29 and 35) records that when the Messiah arrives, He will have the power of Yahweh to open the eyes of the blind, command the crippled to walk, open the ears of the deaf, and raise the dead. What Jesus is recorded as doing in the New Testament is what all the prophets of the Old Testament predicted for the Messiah. I documented the 400 Messianic Prophecies Jesus fulfilled in the New Testament in my book: “The Prophecies of the Messiah.”

There is no necessary “Synoptic Problem” if we read the Gospels for what they claim to be: eyewitness narratives of men who saw and heard Jesus.

The “synoptic problem” exists only under skeptical presuppositions. The historical and manuscript evidence (early papyri, patristic testimony, and internal claims) supports the view that the Gospels are early, accurate, and complementary testimonies—not late, distorted traditions.

See All of the Published Books by Robert Clifton Robinson at Amazon

Sources and Citations

- Is The New Testament A Valid Historical Narrative?

- Legal Analysis Of The Four Gospels As Valid Eyewitness Testimony

- When Were The Gospels Written?

- Were The Four Gospels Written Anonymously?

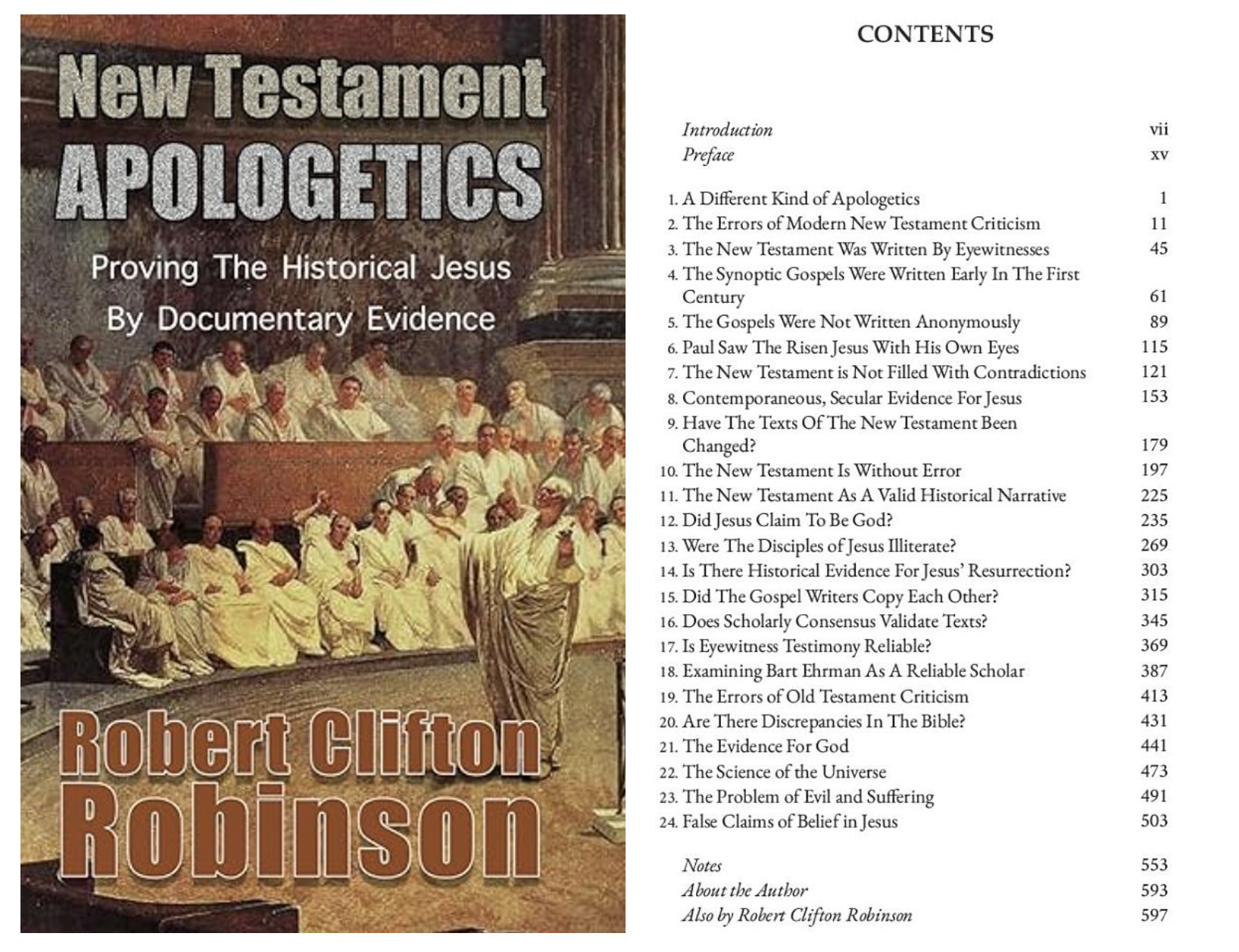

- New Testament Apologetics

- Bultmann, Rudolf. Jesus and the Word (trans. 1958) – quotation cited here:

https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2296/ - Dvorak, James. “Martin Dibelius and Rudolf Bultmann” (overview of form-critical presuppositions, with refs):

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328201590_Martin_Dibelius_and_Rudolf_Bultmann - Ehrman, Bart. “Misquoting Misquoting Jesus” (includes the famous ‘more variants than words’ line):

https://ehrmanblog.org/misquoting-misquoting-jesus/ - Ehrman, Bart. “What I Do Argue in Misquoting Jesus” (no originals; later-generation copies):

https://ehrmanblog.org/what-i-do-argue-in-misquoting-jesus/ - Ehrman, Bart. Jesus Before the Gospels (public PDF excerpt used for short quotation):

https://ia904602.us.archive.org/15/items/apocryphal-gospels-bart-ehrman/Jesus%20Before%20Gospels%20%28Bart%20D.%20Ehrman%29.pdf - Eusebius, *Church History* 3.39 (Papias on Mark/Matthew):

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250103.htm - Irenaeus, *Against Heresies* 3.1.1:

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103301.htm - Bauckham, Richard. *Jesus and the Eyewitnesses* (2006) (searchable PDF copy used for quotation):

https://lecturanarrativadelabiblia.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/jesus-and-the-eyewitnesses.pdf - Bailey, Kenneth. “Informal Controlled Oral Tradition and the Synoptic Gospels” (PDF):

https://www.cairnsroad.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Informal-Controlled-Oral-Tradition-and-the-Synoptic-Gospels.pdf - P46 overview (date ~175–225):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_46 - P66 overview (trad. ca. 200; Bodmer):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_66 - P75 overview (trad. 3rd c.; affinity with Vaticanus):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_75 - Metzger, Bruce M., and Bart D. Ehrman. *The Text of the New Testament*, 4th ed. (2005) – handbook:

https://archive.org/details/TheTextOfNewTestament4thEdit

Categories: Robert Clifton Robinson

Please see, "Guidelines For Debate," at the right-side menu. Post your comment or argument here: