How The Septuagint Confirms The Authenticity Of The Messianic Prophecies Written For Jesus

Does the Septuagint confirm that the Old Testament Prophecies of the Messiah were written and recorded long before Jesus arrived and fulfilled all that were written for Him?

Yes, the Septuagint (LXX) serves as historical evidence that the Old Testament Messianic prophecies were written and recorded long before the birth of Jesus Christ. The following essay lists the key reasons why the Septuagint confirms the pre-existence of these prophecies and their fulfillment by Jesus in the New Testament.

Why Does This Matter?

A common objection by critics of Jesus and the New Testament, is the assertion that Jesus never fulfilled the 400 Messianic Prophecies listed in the Old Testament, because they were written, “after the fact.” In other words, what Jesus is alleged to have done, as recorded in the New Testament, is in reality, the result of someone in the first century fabricating these Messianic Prophecies that matched what Jesus had said or done, then claimed He fulfilled 400 Messianic Prophecies.

What this essay proves, is precisely what history records: The 400 Prophecies of the Messiah, were already in the historical texts of the Bible, long before Jesus was born.

The Historical Dating of the Septuagint

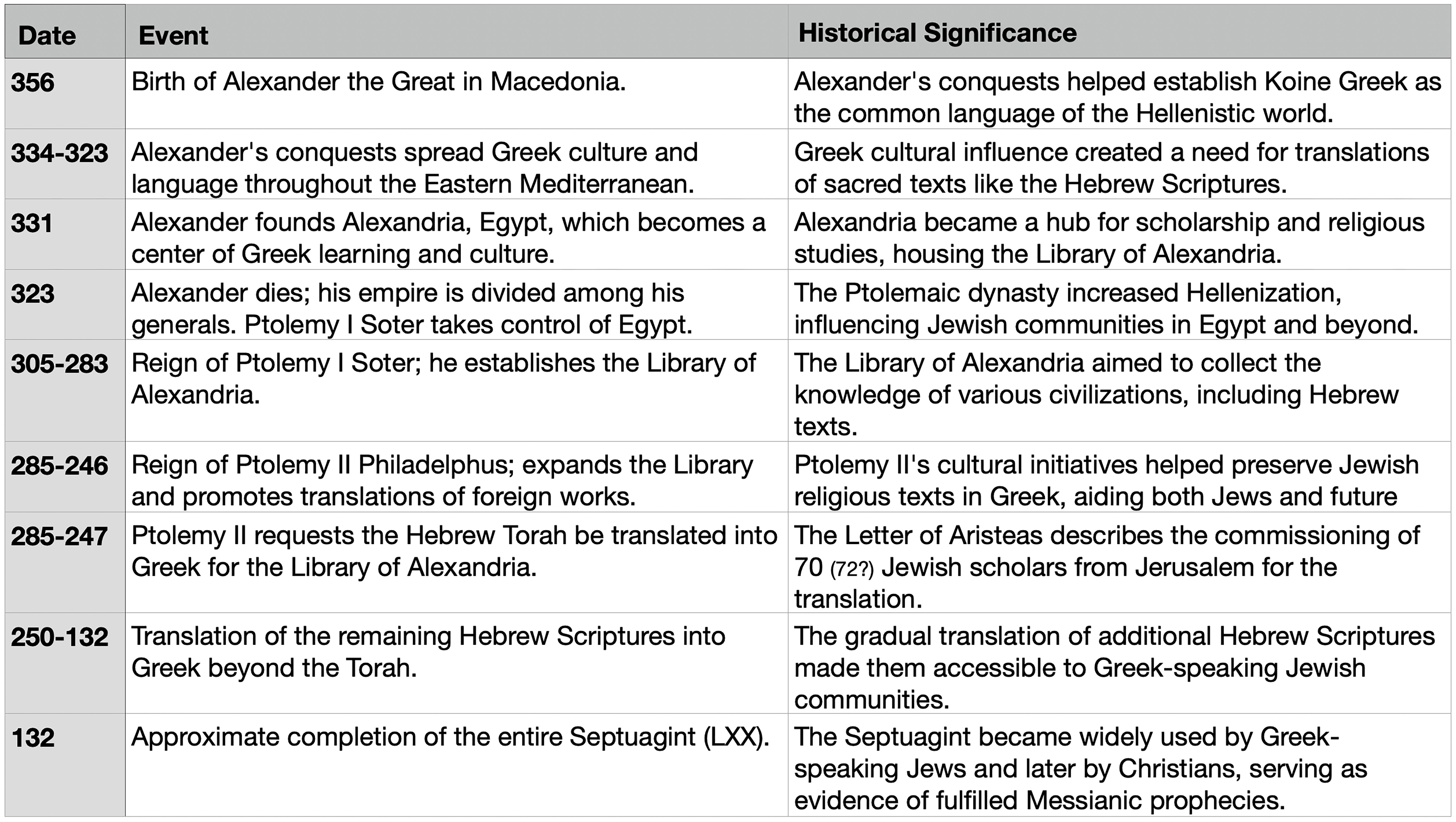

The translation of the Pentateuch (first five books of the Old Testament) occurred between 285-247 B.C. during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in Alexandria, Egypt. The remainder of the Hebrew Scriptures was translated into Greek over the next century, with the entire Septuagint completed by approximately 132 B.C. Since the Septuagint is a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, the original Hebrew texts from which it was translated must have been written centuries earlier.

Confirmation of Messianic Prophecies

The Septuagint preserves numerous prophecies that the New Testament writers identify as fulfilled in Jesus. For example:

Isaiah 7:14 (LXX): “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and you shall call his name Immanuel.” (Greek: παρθένος, parthenos meaning virgin) This word choice confirms that the prophecy of a virgin birth existed centuries before Jesus’ birth, countering the argument that Christians altered the text.

Isaiah 53 (LXX): Describes the Suffering Servant who would bear the sins of many, aligning with Jesus’ crucifixion and atonement.

Psalm 22 (21 LXX): Prophecies regarding the Messiah’s suffering, including pierced hands and feet, casting lots for His garments, and mockery from bystanders.

Micah 5:2 (LXX): Foretells the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem, fulfilled in Matthew 2:1.

Zechariah 9:9 (LXX): Describes the Messiah entering Jerusalem on a donkey, fulfilled in Matthew 21:5 and John 12:15.

The presence of these texts in a Greek translation completed more than a century before Jesus’ birth demonstrates that these prophecies were not retroactively added to align with Jesus’ life.

Use of the Septuagint by New Testament Writers

The New Testament authors, particularly Matthew, Paul, and Luke, often quoted directly from the Septuagint rather than the Hebrew Masoretic Text. For example, when Matthew quotes Isaiah 7:14 (Matthew 1:23), he uses the Greek word parthenos (virgin), aligning with the Septuagint’s wording. This proves that the Greek translation containing Messianic prophecies was widely known and accessible before the time of Jesus, further validating their authenticity.

The Dead Sea Scrolls as Corroborating Evidence

The Dead Sea Scrolls (circa 250 B.C. – 70 A.D.), discovered in the 20th century, include Hebrew manuscripts of Isaiah, Psalms, and other prophetic books. These Hebrew texts match the prophetic content found in the Septuagint, proving that both the Greek and Hebrew versions preserved the same prophecies centuries before Jesus’ birth.

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa), dated to around 125 B.C., contains Isaiah 53 with the same descriptions of the Suffering Servant found in the Septuagint and New Testament.

Testimony of Early Jewish and Christian Writers

Philo of Alexandria (20 B.C. – 50 A.D.) and Josephus (37-100 A.D.) affirmed the antiquity and widespread use of the Septuagint among Jewish communities before the rise of Christianity.

Early church fathers like Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Clement of Alexandria referenced the Septuagint when demonstrating that Jesus fulfilled Old Testament prophecies.

Theological and Apologetic Significance

The existence of the Septuagint prior to Jesus’ birth eliminates the possibility that Christians manipulated Hebrew texts to align with Jesus’ life.

Because the Septuagint was translated by Jewish scholars with no connection to Christianity, its content cannot be accused of Christian bias. This historical reality validates the claim that Jesus’ fulfillment of these ancient prophecies was not coincidental or contrived, but a matter of divine orchestration.

The Septuagint conclusively confirms that the Old Testament Messianic prophecies were written centuries before Jesus Christ. Its historical dating, combined with textual evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls and citations in the New Testament, provides undeniable proof that these prophecies existed long before Jesus fulfilled them. As a result, the Septuagint stands as a key witness to the authenticity and divine inspiration of the Messianic prophecies in the Old Testament.

What was the reason that the Hebrew scriptures were translated into Greek language of the Septuagint?

The Hellenization of the Ancient World

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.), Greek culture and language spread throughout the Mediterranean world, including Egypt, Judea, and other regions where Jewish communities lived. Greek became the lingua franca, the common language used for trade, governance, and intellectual discourse, replacing local languages in many areas.

The Jewish Diaspora in Egypt

A large Jewish population had settled in Alexandria, Egypt, which was founded by Alexander the Great and became a major center of Greek culture and learning. By the 3rd century B.C., many Jews in Alexandria no longer spoke or understood Hebrew fluently, making it difficult for them to read and study the Hebrew Scriptures. To maintain their religious identity and access to their sacred texts, the Jewish community needed a Greek translation of the Scriptures.

Request from Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 B.C.)

According to the Letter of Aristeas, a key historical source (though partly legendary), Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Greek ruler of Egypt, requested a Greek translation of the Hebrew Torah (the first five books of Moses) to be included in the famous Library of Alexandria. The king sought to collect the religious texts of various peoples to enhance the library’s reputation as a center of knowledge.

Preservation and Accessibility of Jewish Faith

The translation into Greek allowed Jews living outside Judea to continue practicing their faith and studying the Scriptures in a language they understood. The Septuagint helped preserve Jewish religious identity in a predominantly Greek-speaking world, ensuring that future generations could maintain their spiritual heritage.

Facilitating Cross-Cultural Understanding

Translating the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek made Jewish beliefs, laws, and prophecies accessible to non-Jews who could not read Hebrew. This openness contributed to the spread of Jewish thought throughout the Greek-speaking world and laid the groundwork for the later spread of Christianity.

Theological Motivation

Jewish scholars sought to provide an accurate and faithful rendering of their sacred texts, ensuring that the translation retained the original meaning and authority of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The Septuagint’s use of precise Greek terminology, such as parthenos (virgin) in Isaiah 7:14, influenced early Christian interpretations of Messianic prophecies, reinforcing the belief that Jesus fulfilled these predictions.

Influence on the New Testament

The New Testament writers, especially the apostles and evangelists, often quoted directly from the Septuagint rather than the Hebrew Masoretic Text. For example, when Matthew cites Isaiah 7:14 in Matthew 1:23, he uses the Septuagint’s wording, supporting the claim that Jesus’ virgin birth fulfilled Old Testament prophecy. The widespread availability of the Septuagint helped early Christians demonstrate that Jesus was the fulfillment of ancient prophecies, making the Gospel accessible to Greek-speaking audiences.

The Primary Reasons The Septuagint Was Written

- Language Shift: Greek became the common language of the Jewish diaspora in Egypt.

- Jewish Diaspora: Many Jews outside Judea no longer understood Hebrew.

- Ptolemaic Request: King Ptolemy II Philadelphus commissioned the translation for the Library of Alexandria.

- Cultural Integration: The Septuagint enabled Jewish communities to maintain their faith while living in a Hellenistic culture.

- Cross-Cultural Impact: The Greek translation made Jewish teachings accessible to both Jews and non-Jews, preparing the way for the spread of Christianity.

The translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek was essential for both the Jewish diaspora and the future Christian Church. By preserving the Messianic prophecies in Greek more than a century before Jesus’ birth, the Septuagint serves as a powerful testament that these predictions were not altered or fabricated after the fact. It stands as an enduring witness to the reliability and divine inspiration of the Old Testament, confirming that Jesus fulfilled the prophecies written long before His arrival.

The Following Chart Illustrates The Timeline Between Alexander The Great, And The Creation of the Septuagint:

Why Was The Septuagint Written In Koine Greek, The Same Language The New Testament Was Written In?

The Septuagint (LXX) was translated into Koine Greek, the common dialect of the Hellenistic world during the period following the conquests of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.). The following is a detailed explanation:

What Is Koine Greek?

Koine Greek (from the Greek word κοινή, meaning common) was the everyday language spoken across the Mediterranean world from around 300 B.C. to 300 A.D. Unlike the classical Greek of Homer or Plato, Koine Greek was a simplified, more accessible form of the language, making it easier for people from different regions to communicate. It became the lingua franca (common language) of the Hellenistic world, used for trade, government, and literature.

Why Was the Septuagint Written in Koine Greek?

By the time the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek (circa 285–132 B.C.), Koine Greek had become the dominant language of Alexandria, Egypt, and much of the Eastern Mediterranean. Since the primary audience for the Septuagint was the Jewish diaspora living in Greek-speaking regions, the translators chose Koine Greek to make the Scriptures accessible to as many people as possible. Using a more classical or literary Greek would have limited the translation’s reach, while Koine Greek ensured that both the educated elite and common people could understand the text.

Characteristics of Koine Greek in the Septuagint

- Vocabulary: The Septuagint often uses everyday vocabulary familiar to ordinary people, making the text more relatable.

- Syntax and Grammar: The grammar is generally simpler than classical Greek, reflecting the spoken language of the time.

- Semitic Influence: Due to its Hebrew source material, the Septuagint contains Hebrew idioms and structures that were not typical of native Greek writing. This gave the translation a unique flavor, sometimes called “Jewish Greek.”

- Religious Terminology: Many Greek words used in the Septuagint later influenced Christian theology and the New Testament. For example:

—Kyrios (κύριος) for Lord (The same as “LORD”, Yahweh, in the Old Testament)

—Christos (Χριστός) for Messiah/Anointed One

—Sōtēr (σωτήρ) for Savior

The Link Between the Septuagint and the New Testament

The New Testament was also written in Koine Greek, and its authors frequently quoted directly from the Septuagint. Because both the Septuagint and the New Testament used the same dialect, early Christians could easily see the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies in the life of Jesus Christ.

Examples of Koine Greek Used To Confirm Messianic Terms:

- Isaiah 7:14 – parthenos (παρθένος, virgin) as quoted in Matthew 1:23

- Psalm 22:16 – Reference to pierced hands and feet, aligning with the crucifixion in the Gospels

The Historical and Cultural Context Of Koine Greek

The use of Koine Greek reflected the broader cultural integration of Jewish and Greek worlds during the Hellenistic Period. It allowed Jewish communities living outside Judea to remain connected to their faith, even as they adopted the Greek language and culture.

The Septuagint was written in Koine Greek, the common language of the Hellenistic world. This choice made the Hebrew Scriptures accessible to a broader audience, including the Jewish diaspora and, later, early Christians. Because the New Testament was also composed in Koine Greek, the Septuagint became the primary Old Testament text quoted by the New Testament authors, providing continuity between the Old and New Covenants.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and the commissioning of the Hebrew Scriptures’ translation into Koine Greek in the Library of Alexandria. Copyright, RCR

What are the historical citations and sources for the request by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, to have the Hebrew Texts translated into Greek. Was this a result of Alexander’s actions or Ptolemy?

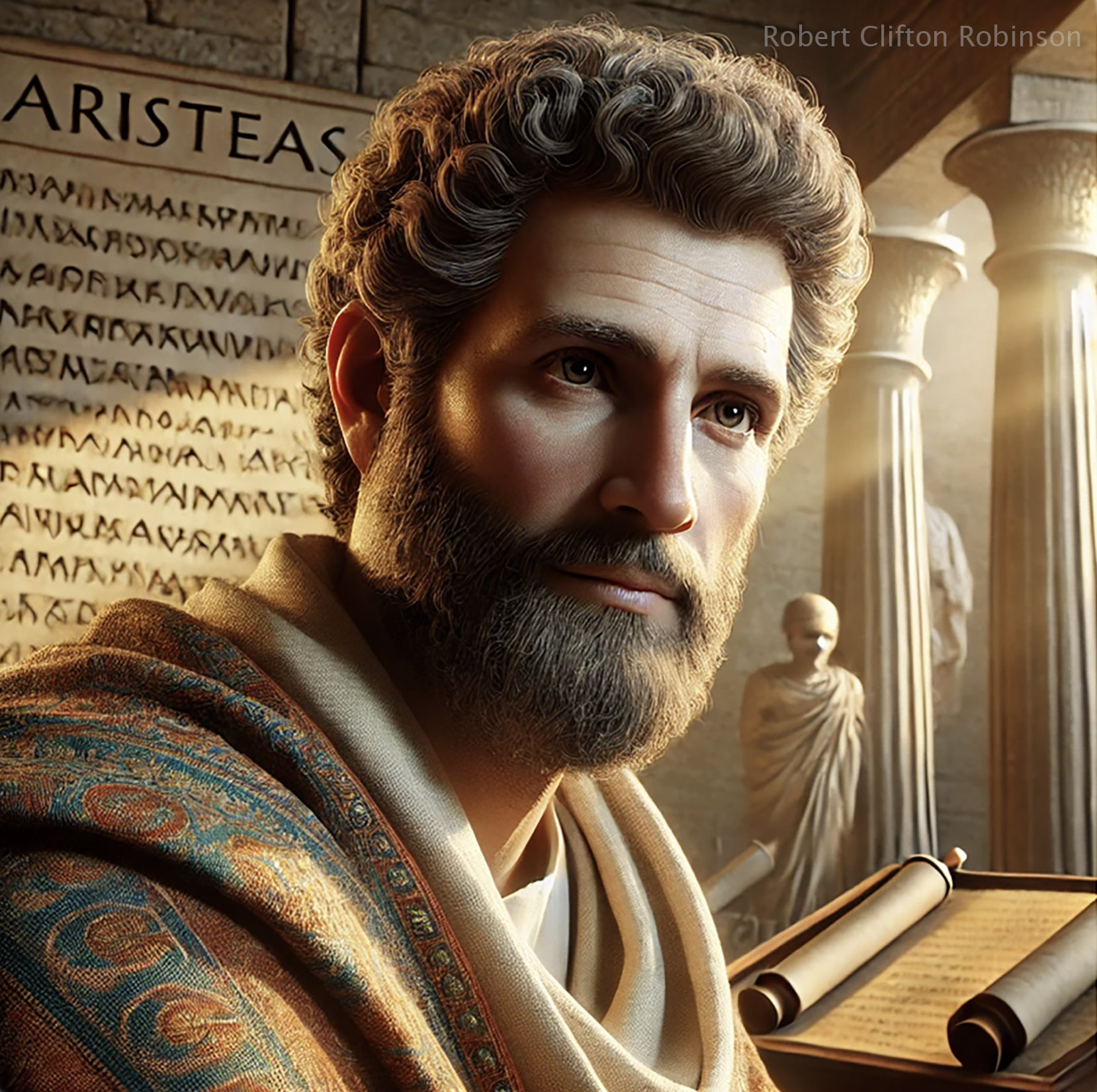

The Letter of Aristeas (2nd Century B.C.): The Letter of Aristeas is the principal ancient source that describes how Ptolemy II Philadelphus commissioned the translation of the Hebrew Torah (Pentateuch) into Greek for inclusion in the Library of Alexandria.

According to this letter, Ptolemy sent envoys to the Jewish high priest, Eleazar in Jerusalem, requesting that seventy-two Jewish scholars—six from each of the twelve tribes—be sent to Alexandria to complete the translation. The letter claims that the scholars completed their translation in seventy-two days and that the result was so perfect that all the scholars agreed on every word, validating its divine accuracy.

Reference: The Letter of Aristeas, Sections 30–50, in R.H. Charles, The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913).

The Letter of Aristeas

The Letter of Aristeas, provides us with the historical account of how the Hebrew Torah was translated into Greek during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 B.C.). This document is essential for understanding the origin of the Septuagint (LXX).

This letter is traditionally attributed to Aristeas, a Greek official at the court of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. It describes how the king requested the Hebrew Torah to be translated into Greek for inclusion in the Library of Alexandria and how 70 Jewish scholars from Jerusalem completed the translation.

Full Text

“To my brother Philocrates,

I have written this account with the greatest care so that you may know the events which led to the translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. It was during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, king of Egypt, that this remarkable undertaking was accomplished.

Ptolemy, having inherited the kingdom from his father, sought to collect all the books of the world into the Library of Alexandria. When Demetrius of Phalerum, the librarian, informed the king that the laws of the Jews were written in Hebrew and had not yet been translated into Greek, the king resolved to have them translated to enrich his library.

Ptolemy wrote to Eleazar, the high priest of the Jews in Jerusalem, requesting that six elders from each of the twelve tribes of Israel be sent to Alexandria to undertake the translation. The king also sent lavish gifts, including gold vessels and precious materials, to demonstrate his respect for the Jewish people and their laws.

Upon receiving the king’s letter, Eleazar carefully selected seventy-two men of great wisdom and virtue, skilled in both Hebrew and Greek. These men were sent to Alexandria with a copy of the Hebrew Scriptures written on gold-embellished parchment.

Upon their arrival, King Ptolemy welcomed them with great honor and held a grand banquet in their honor. During the feast, the king questioned the scholars on matters of philosophy, law, and governance, marveling at their wisdom. Their answers demonstrated the depth of Jewish knowledge and morality, earning the king’s admiration.

The scholars were then taken to a secluded island where they could work without interruption. Each of them independently translated the Torah from Hebrew into Greek. After seventy-two days, their translations were compared, and to everyone’s amazement, they were found to be identical in every detail. This remarkable agreement was seen as evidence of divine guidance, ensuring the accuracy and fidelity of the translation.

When the work was completed, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures was read aloud before the king and his court. Ptolemy, deeply impressed by the beauty and wisdom of the laws, declared that the translation should be preserved with the utmost care. The scholars were sent home with rich gifts and the gratitude of the king.

This translation, known as the Septuagint, has since become a vital resource not only for the Jews of the Diaspora but also for those who seek to understand the ancient wisdom contained in the Hebrew Scriptures. May this account bring you insight into the providence and purpose behind this extraordinary work.”

—Aristeas

The Historical Significance:

The Letter of Aristeas is the primary source for the origin of the Septuagint (LXX) and explains why the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Koine Greek. This translation took place in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus.

- The importance of preserving sacred texts in a language accessible to Greek-speaking Jews.

- The recognition of Jewish wisdom and morality by the Greek world.

- The inspiration provided by the God of the Bible that guided the translation process.

- The translator’s role in promoting understanding between Jewish and Greek cultures.

Flavius Josephus (37–100 A.D.)

The Jewish historian Josephus repeats the account found in the Letter of Aristeas, emphasizing the role of Ptolemy II Philadelphus and the collaboration between Jewish scholars and Egyptian authorities. Josephus highlights that Ptolemy sought to include the Jewish Scriptures in his vast library, reflecting the Hellenistic interest in collecting the knowledge of various cultures.

Reference: Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XII, Chapter 2, translated by William Whiston (Hendrickson Publishers, 1987).

Philo of Alexandria (20 B.C. – 50 A.D.)

The Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, who lived in the same city where the translation was produced, affirmed the divine nature of the Septuagint. Philo believed that the translation process was guided by divine inspiration, lending it authority and sanctity within the Jewish diaspora.

Reference: Philo, Life of Moses, Book II, 25-44, in The Works of Philo, trans. C.D. Yonge (Hendrickson Publishers, 1993).

Epiphanius of Salamis (310–403 A.D.)

Epiphanius, an early Christian bishop and scholar, provided a more detailed account of the translation process, although his version includes legendary embellishments. He reiterates that Ptolemy II Philadelphus initiated the project as part of his broader efforts to collect and translate the world’s knowledge into Greek.

Reference: Epiphanius, De Mensuris et Ponderibus (On Weights and Measures), Sections 9-11.

The Historical and Cultural Context: Alexander vs. Ptolemy

Alexander the Great’s Role: Alexander’s conquests (334–323 B.C.) spread Greek language and culture across the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, creating the linguistic environment that necessitated the Greek translation of Hebrew Scriptures. The city of Alexandria, Egypt, founded by Alexander, became a center of Hellenistic culture and intellectual activity, housing the famous Library of Alexandria.

Ptolemy II Philadelphus’ Role: After Alexander’s death, his empire was divided among his generals, with Ptolemy I Soter (367–283 B.C.) taking control of Egypt, establishing the Ptolemaic Dynasty. His successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, expanded the cultural and intellectual pursuits of his father, including commissioning translations of foreign works into Greek. Ptolemy II’s specific request for the Hebrew Scriptures reflected both his desire to enrich the Library of Alexandria and his diplomatic relationship with the Jewish community in Egypt.

Reference: Naphtali Lewis, Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986).

Influence of the Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria was intended to collect and preserve the knowledge of all known civilizations, making translations like the Septuagint essential. Under Ptolemy II, scholars sought to gather authoritative texts from different cultures, including Egypt, Greece, Persia, and Israel.

Reference: Lionel Casson, Libraries in the Ancient World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001).

Scholarly Analysis of the Septuagint’s Origin

Sidney Jellicoe and Martin Hengel, leading modern scholars, confirm that while the account in the Letter of Aristeas contains legendary elements, the core historical facts are reliable. The translation’s production in Alexandria during Ptolemy II Philadelphus’ reign is widely accepted by historians, with the broader context of Hellenization initiated by Alexander the Great.

References:

- Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968).

- Martin Hengel, The Septuagint as Christian Scripture (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2002)

The translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek was commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphus during his reign (285–246 B.C.), primarily to include the Jewish Torah in the Library of Alexandria and to provide Greek-speaking Jews with access to their sacred texts.

While the broader linguistic and cultural context was shaped by Alexander the Great’s conquests, the specific initiative to translate the Hebrew Scriptures was a distinct action taken by Ptolemy II as part of his efforts to promote learning and diplomacy within his realm.

The primary historical sources supporting this event are the Letter of Aristeas, Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, and references from Philo of Alexandria and Epiphanius of Salamis.

Examining The Historical Record That Documents The Translation Of the Hebrew Scriptures Into Koine Greek

The Septuagint (LXX) is the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament), and it holds immense historical and religious significance. Here’s a detailed historical background regarding its origin, time, place, and the scholars involved in its composition:

Time of Composition

The translation of the Pentateuch (the first five books of Moses) occurred around 285-247 B.C. during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.) in Egypt. The translation of the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures followed gradually over the next century, completed by roughly 132 B.C. or slightly later.

Place of Composition

The translation was undertaken in Alexandria, Egypt, a thriving center of Hellenistic culture and learning. Alexandria’s large Jewish community—estimated at several hundred thousand—was becoming increasingly Hellenized, prompting the need for a Greek version of the Hebrew Scriptures, as many Jews no longer spoke Hebrew fluently.

Scholars Involved

According to tradition, Ptolemy II Philadelphus requested the translation for inclusion in the renowned Library of Alexandria. The Letter of Aristeas, a key historical source (though partly legendary), claims that 70/72 Jewish scholars—six from each of the twelve tribes of Israel—were commissioned for the work. This tradition is the origin of the name Septuagint, derived from the Latin word for seventy, septuaginta.

The scholars chosen were deeply knowledgeable in both Hebrew and Greek, ensuring the accuracy and fidelity of the translation.

Historical and Cultural Context

The translation occurred within the broader context of the Hellenistic Period, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. His empire spread Greek culture, language, and influence across the ancient world. As Greek became the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures became essential for both the Jewish diaspora and non-Jews interested in Judaism.

The Septuagint later played a critical role in the spread of Christianity, as early Christians, including the authors of the New Testament, frequently quoted from the Greek text when referencing the Old Testament.

Authorship and Process

The process began with the translation of the Torah (Pentateuch), regarded as the most sacred part of the Hebrew Scriptures. Over the next century, other books of the Hebrew Bible, as well as additional Jewish writings, were translated into Greek.

Unlike the Pentateuch, which was carefully translated by Jewish scholars adhering closely to the Hebrew text, some of the later books exhibit more interpretive freedom, reflecting the translators’ cultural and linguistic context.

Influence and Legacy

The Septuagint became the authoritative version of Scripture for Greek-speaking Jews in Egypt and throughout the Hellenistic world. Early Christians adopted the Septuagint as their primary Old Testament text, seeing in it numerous prophecies fulfilled in Jesus Christ. The New Testament writers often quoted directly from the Septuagint, shaping the theological language of Christianity.

Modern Scholarly Perspectives

Contemporary scholars recognize the Septuagint as more than a simple translation—it reflects the theological interpretations and textual variations present in the Jewish communities of its time. Manuscripts such as the Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Alexandrinus—dating from the 4th and 5th centuries A.D.—preserve large portions of the Septuagint, enabling modern scholars to study its textual history.

- Time: Circa 285-247 B.C. (Pentateuch), completed by approximately 132 B.C.

- Place: Alexandria, Egypt

- Scholars: Traditionally, 72 Jewish translators chosen from each of Israel’s twelve tribes

- Purpose: To provide Greek-speaking Jews access to their sacred texts and for inclusion in the Library of Alexandria

The following are credible historical sources and citations supporting the facts about the origin, time, place, and scholars involved in the writing of the Septuagint:

Primary Ancient Sources:

Letter of Aristeas (circa 2nd century B.C.): The primary ancient source regarding the Septuagint’s origin.

- This letter describes how Ptolemy II Philadelphus invited 70 Hebrew scholars from Jerusalem to Alexandria to translate the Hebrew Torah into Greek for the Library of Alexandria.

- English Translation: R.H. Charles, “The Letter of Aristeas” (Oxford, 1913).

Philo of Alexandria (20 B.C. – 50 A.D.)

- A Hellenistic Jewish philosopher from Alexandria who affirmed the divine inspiration of the Septuagint and its translation process.

- Reference: “Life of Moses,” Book II, 25-44, in The Works of Philo (trans. C.D. Yonge, Hendrickson Publishers, 1993).

Josephus, Flavius (37–100 A.D.)

- Jewish historian who reiterated the account found in the Letter of Aristeas.

- Reference: “Antiquities of the Jews,” Book XII, Chapter 2, in The Works of Josephus (trans. William Whiston, Hendrickson Publishers, 1987).

Epiphanius of Salamis (310–403 A.D.)

- Church father who expanded on the story of the Septuagint, though with legendary embellishments.

- Reference: “De Mensuris et Ponderibus” (On Weights and Measures), Section 9-11.

Secondary Scholarly Sources:

Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968): A comprehensive analysis of the Septuagint’s textual history, linguistic features, and its influence on Judaism and early Christianity.

Martin Hengel, The Septuagint as Christian Scripture: Its Prehistory and the Problem of Its Canon (Baker Academic, 2002) He Examines the historical context of the Septuagint, including its use by Hellenistic Jews and early Christians.

Karen H. Jobes and Moisés Silva, Invitation to the Septuagint (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2000): A modern introduction to the Septuagint’s historical background, linguistic significance, and canonical role.

James Barr, The Typology of Literalism in Ancient Biblical Translations (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1979): Discusses the translation techniques and methodologies of the Septuagint translators.

Manuscript Evidence:

- Codex Sinaiticus (4th century A.D.) – Preserved in the British Library, London.

- Codex Vaticanus (4th century A.D.) – Preserved in the Vatican Library, Rome.

- Codex Alexandrinus (5th century A.D.) – Preserved in the British Library, London.

These ancient codices contain large portions of the Septuagint, confirming its textual transmission.

Timeline and Hellenistic Context:

Ptolemy II Philadelphus (283–246 B.C.): His reign corresponds with the earliest phase of the Septuagint’s translation:

Reference: Naphtali Lewis, Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), which discusses the cultural and intellectual environment of Alexandria during Ptolemaic rule.

Hellenistic Influence: The spread of Greek culture and language after the conquests of Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.) created the necessity for Greek translations of Hebrew texts.

Reference: Erich S. Gruen, Heritage and Hellenism: The Reinvention of Jewish Tradition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

Key Citations:

- Letter of Aristeas, Sections 30–50

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, XII.2

- Philo of Alexandria, Life of Moses, II.25–44

- Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study, pp. 1–42

- Martin Hengel, The Septuagint as Christian Scripture, pp. 1–56

The confirmation of the Septuagint, containing 400 of the Old Testament Messianic Prophecies, documented as fulfilled in the New Testament, is a significant proof for the reliability of the New Testament. The eyewitness, historical testimony about Jesus is further validated by the reliability and historical preservation of prophecies written for Jesus—preserved in the Septuagint Version of the Bible.

See Rob’s Detailed Treatise On The Eyewitness, Historical Evidence, That Documents The Reliability of the New Testament

“New Testament Apologetics: Proving The Historical Jesus By Documentary Evidence”

Categories: Evidence: Messianic Prophecies, Messianic Prophecies, Messianic Prophecy Bible, Messianic Prophecy Confirmed by the Septuagint, New Testament Apologetics, Old Testament Apologetics, Prophecies Fulfilled by Jesus, Prophecy, Prophecy proven by History, Reliability of the Bible, Robert Clifton Robinson, Secular Sources for Jesus, The Historicity of Jesus, The Importance of the Bible, The Prophecies of the Messiah, The Septuagint

Please see, "Guidelines For Debate," at the right-side menu. Post your comment or argument here: